Lowell Daily Mail, 11/14/1902

The history and spirit of a place is found in its architecture. Yet Lowell was initially built as a place to make wealth, not display it. Tentative and experimental, it was a provisional place for its parsimonious Yankee founders, where financial failure was a constant specter. People came and left with regularity. They built only what was necessary — and then only plainly and conservatively. The one exception, Kirk Boot’s imposing house, was re-used after his death as a worker’s hospital, an eminently more practical use for the large mansion.

But even from its beginning, Lowell also attracted ambitious builders, merchants, and tradesmen who, along with the local farmers and speculating landowners, saw it as a home and a community, independent of the all-powerful Boston investors, and something more than the proto-typical company town. By the mid-1840s, they began to display their new prosperity in impressive homes on the edges of the expanding city. The corporations kept a tight control on the city’s budget and expenditures through their Whig allies who dominated the local government. But the local grandees, mostly Democrats, working with their county allies, provocatively built an alternative civic center on the southern end of the town. There, overlooking the new South Common, and facing each other as poles on an east-to-west axis, they raised a handsome courthouse and a monumental jail. This extravagance vexed their opponents. The local bar association refused to dedicate the new courthouse, and the architectural grandeur of a lowly jail was roundly condemned. Meanwhile the Whigs sidestepped past a much-needed new city hall by throwing up a drafty, structurally unsound barn of a hall over a smoky train depot, shoehorning in shops to pay for its upkeep.

But the 1857 scandal of Samuel Lawrence’s embezzlement from the Middlesex Mills of Lowell and the Bay State Mills in Lawrence and the disastrous mismanagement of the mills during the Civil War emboldened locals to fight for greater economic independence. In the aftermath, local manufacturers and business owners built railroads, impressive new business blocks, locally capitalized factories, and elegant new homes in the Highlands to the west, as well as on Pawtucket Street and the along the slopes of Christian Hill. In response, the corporations moved their managers from the city’s core to Nesmith and Andover Streets in leafy, rural Belvidere.

This transformation continued, and by the early 1890s, at the height of the Gilded Age, Lowell was rapidly acquiring the symbols and necessities of a major, thriving metropolis. Within a few short years it gained a monumental new city hall, a modern library, several other civic facilities, numerous substantial commercial blocks, a controversial new post office, a stylish union railroad depot, multiple parks, a racing boulevard to match the one in Boston, new churches and social clubs, a grand high school, and an impressive normal school. The city was reimagined seemingly overnight, and kicking off this building frenzy was one extraordinary house that exemplified all the new confidence and bravura of the time: Mr. Faulkner’s “Castle” high atop a precipitous hill in the increasingly rarified zone of Belvidere Heights.

Mr. Faulkner’s House, Lowell Daily Courier

But to properly tell the story of Frederic Faulkner and his extraordinary house, we must start with Captain William Wyman and his folly. The eccentric Captain William Wyman, one of Lowell’s earliest independent capitalists, acquired the 43-acre “Lynde Hill Estate” on the eastern extreme of Belvidere Village in 1841. A self-proclaimed preacher, he was also a savvy businessman. Always idiosyncratic, he built a homely row of five houses and barns, interconnected and indistinguishable from one another, at the head of today’s Wyman Street. He experimented and failed with growing peaches and then wine grapes. But Wyman’s peace on the hill was disrupted in 1849 by the construction of a reservoir next door. Crowds flocked up the hill to stroll about the reservoir and marvel in the grand view, inspiring in Wyman his great quixotic vision of a soaring observation tower on the summit of the hill, rising 150 feet and adorned with 27 busts of prominent figures. In another flash of inspiration, he called it the “Appleton Observatory,” futilely hoping that investor Nathan Appleton would become a major donor. To entice subscribers, he put a lithograph of his observatory on view in the window of Merrill’s bookstore on Merrimack Street. But the scheme languished.

Ever hopeful, Wyman tried once more in 1863 with the renamed “Washington Observatory.” This time he got as far as a foundation on the eastern side of today’s Belmont Avenue, but he died the next year. The Washington Observatory plans, if not the idea of a tower, died with him. For years after, the abandoned foundation was known as “Wyman’s Folly” or simply “the old castle.” Wyman’s son Samuel subdivided the property into 214 house lots but the desolate, steep hill was poor competition for the burgeoning Highlands neighborhood to the west. One of the few early buyers was Alexander Cumnock, the agent for the Boot Mills, but when Samuel died in 1883, his estate fell to a tangled mess of heirs.

But that hill and its sweeping views could still inspire recklessness, and in 1887 two wealthy brothers, John and Frederic Faulkner, laboriously acquired large house sites from the scattered heirs (including a grandson confined to an insane asylum in Providence.) Their house lots, perhaps provocatively, bookended Cumnock’s new house. The Faulkners were longtime woolen manufacturers. John and Frederic’s father Luther Faulkner began woolen manufacturing in Billerica and expanded to Lowell in 1865. The brothers joined the family partnership and for years lived in modest company-owned houses on Faulkner Street close by the family mills. Nothing about them hinted at the extravagant display of wealth that would come.

John Faulkner House, 1887 W. Whitney Lewis, Architect

John built his new home first, on the corner of Hovey and Belmont. He chose the Boston architect W. Whitney Lewis to design a handsome house in the most up-to-date Shingle Style, like the great cottages of the North Shore that Lewis had designed for Boston socialites. It was and is the best example of Shingle Style in Lowell and one of the best in Massachusetts. And without question, John now had finest and most fashionable house in the city. But the distinction lasted for only a short time, because the following year, his older brother Frederic built his own showstopper.

Bradbury House, 1887 Back Bay Boston, W. Whitney Lewis, Architect; American Architect and Building News.

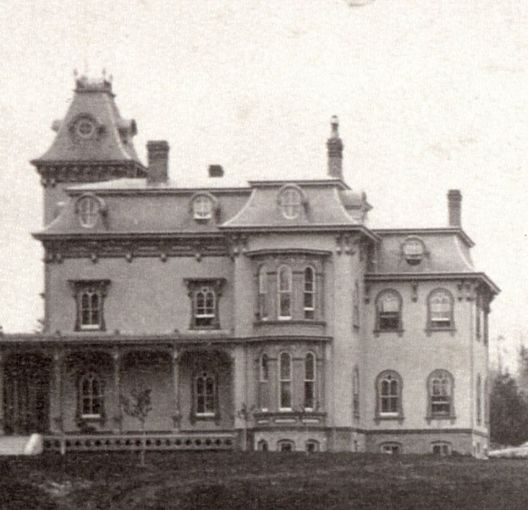

Frederic also chose W. Whitney Lewis, perhaps impressed by the house Lewis had built for Dr. Bradbury in Boston the previous year. A palatial house like that was noteworthy yet not out of place in Boston, but it was unprecedented for a place like Lowell. And yet Faulkner built what would become his own folly, on the very site of Wyman’s Folly; a new castle on top of the old castle, and this one at last would have a tower, an observatory. It was the most ostentatious house Lowell had ever seen . It reportedly cost over $125,000 to build and furnish, which is around $3,000,000 today, and despite that exorbitant sum the interior was not completely finished. Even at the height of the Gilded Age, no one could expect he would ever recover his investment. The house took two years to build and it became an instant landmark widely recognized far beyond Lowell. You could admire the mountains of New Hampshire from that tower and the admiration was mutual. The Grand Hotel in Mont Vernon, New Hampshire, boasted that you could see Mr. Faulkner’s Castle from the hotel’s piazza.

Frederic Faulkner House, 1888, W. Whitney Lewis, Architect

Whitney’s design was full-blown Richardsonian Romanesque, a style then at the height of its popularity. It was built entirely of pink North Conway granite, a stone quite similar to the pink Milford granite that the master H.H. Richardson favored. The monochromatic effect gave the building a modern aesthetic that must have influenced Lowell’s City Hall Commission a year later, when the members insisted that the new City Hall also be built in granite. In fact it was built with the same North Conway stone. Faulkner’s house initiated a building spree over the next three years.

The economic chaos of the Panic of 1893 brought the building frenzy to a standstill, and Chicago’s great Columbian Exposition of the same year brought about a revolution in architectural style that made Lowell’s new landmarks instantly out of fashion. Then just six years after the castle’s completion, the unthinkable happened. At 1:00 am on August 17th 1896, Michael Martin, coachman for Alexander Cumnock, was awakened by a loud cracking and dogs barking. Expecting to find a burglar, he looked out to see the Frederic Faulkner’s house in flames. Martin raced to John Faulkner’s house to rouse him.

Fortunately, there was no one home at Frederic’s; the family was away in Scituate. An alarm was called from Box 41. The pumper strained up the steep hill but arrived to find the house totally engulfed in flames. More alarms followed, and additional companies labored up to join the fight. And then at 1:30, all at once, the front of the house collapsed. Several firefighters were struck and injured by the rain of falling slates. Neighbors watching from the porch of the house across the street fled the intense heat as the house behind them was scorched. By 3:00 am the great tower was “an immense beacon lighting the heavens” The flames lit up the night sky for miles around. The fire chief ordered the unstable walls knocked over. At last, at 6:30 am, the recall was sounded, and weary firefighters returned to their station houses leaving a skeleton crew on watch. The interior of the house was nothing but ash and cinders, and only the porte cochere remained unharmed.

The fire was news across the country. Thousands climbed the hill to take in the scene, and rumors of arson ran rampant. Some reported seeing a basement window open earlier in the day. The neighborhood had also recently been pestered by petty thieves. The Faulkner Mills had had their own labor problems recently, perhaps inspiring resentment or maybe burglars had torched the house to hide their crime. This would all become apparent when a safe was found, because there had to be one.

But when a stunned and shaken Frederic arrived in Lowell from Scituate that evening, he explained that there was no safe in the house. As for arson, he couldn’t conceive of such a thing; no one could have such animosity towards him or his family. Yet he was no stranger to fire. In 1880 the family’s mills were destroyed in what was one of the most memorable fires in Lowell history, only to be rebuilt immediately.

Of course, the good silver had been stored at his brother’s house for the summer, but his best watch and chain, Mrs. Faulkner’s better jewelry and wardrobe, and the furniture and invaluable paintings were all gone in the inferno. The loss was estimated at $100,000, but the insurance on the house was only $60,000, and the contents were also underinsured. Yes, he shakily responded to the inevitable question, he would rebuild, but how and what he couldn’t say just now.

Meantime Faulkner retreated to more modest quarters in the Highlands, and the ruins languished for three years with no attempt to rebuild. Fortunes and circumstances were changing rapidly for the Faulkners. The Faulkner family partnership was reorganized in 1897 as a corporation, and in April of 1899, it was absorbed by the American Woolen Company, the huge conglomerate of woolen mills spread across four states and headed by Frederick Ayer and his son-in-law William Wood. Brother John stayed on as the agent for the Lowell operation, but the Faulkner name was removed and the plant was rechristened the “Bay State Mills,” coincidentally the same name as that of the company Samuel Lawrence had ruined forty years earlier.

Frederic took the Faulkner name for a new venture, a woolen factory in Stafford Springs, Connecticut, which he started that same year in a leased mill. So, in September 1899, three years after the fire, he offered the ruins for sale at auction, but there were no buyers — or at least none willing to pay Faulkner’s price — and so he waited another two years. In September of 1901, with even more reason to sell, he tried again and this time managed to sell the ruins and an adjoining lot to William T. White for $8,000, a sum equal to the value of a mortgage on the property. White began reconstruction almost immediately in October, first taking down the ruined walls and then building a more modest version of the original house five years after the fire. This is what we see today. Conspicuously, the hubristic tower was not rebuilt, but this would not be the end of the story.

William T. White Reconstruction of the Faulkner House, 1902

White was much like Faulkner. He was the son of a local self-made industrialist, and he worked in the family firm White Brothers and Sons, a tannery complex on Perry Street soon to be swallowed by the huge conglomerate American Hyde and Leather. White and Faulkner certainly were well acquainted, but White clearly didn’t share Faulkner’s boldness or appreciate his urgency to be disentangled from Lowell. So when he bought the house site, he deferred on buying the rest of Faulkner’s land. He said he’d think about it but he thought Faulkner’s price was too high. Impatiently waiting for another two years and growing tired of seeing unproductive land taxed (although he didn’t pay the taxes,) Faulkner devised a scheme to prod the indecisive White. On October 13, 1903, White and stunned neighbors woke up to what the press gleefully called the “Siege of Quality Hill.” Faulkner had thrown up on the adjoining lot the first of a threatened forty prefabricated cottages, shanties really, threatening to make the castle an architectural Gulliver engulfed by slapdash Lilliputians.

Neighbors were scandalized. They’d always thought of Mr. Faulkner as a pleasant neighbor, and this ungentlemanly business was out of character with the charitable leader they remembered. But Faulkner’s circumstances had changed. He had been separated from his wife since 1901, and his brother John had sold his own elegant house the previous year to Fred C. Church for $14,000, once again the value of the mortgage. As the days passed and White dithered, Faulkner increased the pressure, first by building a fence along the property line that blocked White’s access from the back door and then letting it be known that he even tried to hire two different Lowell architects to remodel his stable into a 12-unit tenement. ( Both had politely refused.) Technically speaking, none of this was Faulkner’s doing. He’d transferred the properties to John J. Haskell, a local lawyer, but everyone knew that Haskell was Faulkner’s fixer. The press delighted in the discomfort of the swells on Belvidere Heights.

Lowell Daily Courier 11-17-1902

The impasse ended anticlimactically in May of the following year, when White bought the lots with a mortgage from Faulkner’s father. Significantly, White’s reconstructed house would be the last of the great houses of the Gilded Age to be built in Lowell. The debacle on the Heights had proved that the economics of these houses in this town were unsound, and the age of the big house, it was declared, was over.

Now firmly established in Stafford Springs as a local business leader and sporting gentleman, Faulkner rented “Woodlawn” on Highland Terrace in 1902, the grandest house in town and possibly all of Tolland County.

Woodlawn, Stafford Springs

But it would be no happy substitute for the family; Faulkner sued his wife Emma for divorce in late 1904. His claimed abandonment arguing his wife had refused to leave Lowell and follow him to Connecticut. The decree was issued on December 21, 1905 but Faulkner was not lacking for company because just a month later in January of 1905, he remarried, this time to a former English housemaid, thirty years his junior. Several years later, he built a more modest house for his new bride in a prominent location overlooking his Connecticut mills.

Faulkner’s modest “bungalow’ was prominent enough to warrant a post card.

The Faulkner Bungalow in 2019

Once again in 1913 fire stalked Faulkner destroying his Stafford Springs mills. This fire was indisputably arson. It was started in three different locations and conveniently the hydrants had been shut off. Faulkner leased but didn’t own the mill buildings and they had fallen into receivership. This time an uncertain Faulkner wasn’t sure he’d rebuild and he sold his machinery in 1916 and died in 1925 and perhaps not surprisingly, he didn’t warrant an obituary in the Boston Evening Transcript, the journal of the Boston Brahmin elite. Coincidentally, Woodlawn, the great house, now owned by the town was torched by an arsonist in 1929 and burned to the ground.

Excellent!

Jonathan

>

LikeLike

What a wonderful story. I grew up in the neighborhood and as a child, loved the architecture, but never heard the stories. Thanks again

LikeLike

Thanks. It’s been interesting and fun to rediscover these stories.

LikeLike

This was a riveting read. Lowell’s history has always transfixed me. The city’s history has seemed to me to be more about personalities than fortunes. Of course, one could say all history is, but for me, it’s similar to reading a great novel with your family serving as the fictional framework. Thank you so much for this research and for sharing your efforts.Great job.

LikeLike

Raised in Belvidere, but not among the mansions, I would walk their neighborhoods fascinated by the beautiful big homes. It is great to get some history on their origins and architecture. Thank you.

LikeLike

This is quite a story! It was impossible to put down until I finished. To Connecticut for July 4, not far from Stanford Springs, I may visit there. I wonder if any of the ‘modest cottage’ remains.

Thank you Joe, for reporting and sharing this very interesting history.

LikeLike

It’s still there Sarah! I took that photo this Spring. Up the hill behind the Episcopal Church.

LikeLike

Thanks Joe, as a painting contractor in Lowell for 38 years, I’ve had the opportunity to work both in and out of many of these majestic beauties. Terrence Gormley

LikeLike

Born and brought up in Lowell, but now a NJ resident for the past 50 years, I love reading all the stories of the past. I love Lowell and always will. Are there any books available today with articles like this one above?

LikeLike

Hi Muriel,

There are no histories that I’m aware of that cover the topics that I’ve researched ad written about. There are a number of old=school histories of Lowell, many of them are available on line and there are a number of more recent academic history of labor and related topics. A good place to start is here:

https://libguides.uml.edu/early_lowell/home

Also Richard Howe’s Blog includes a lot of topics on Lowell history that you would enjoy. RichardHowe.com

LikeLike