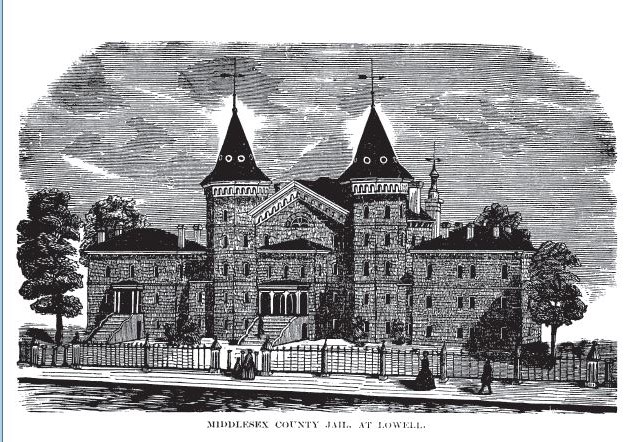

Who was the architect of two of the most sophisticated houses of Lowell’s first half-century? When I came across a credit for the architect of the two houses, I knew I wanted to know more about him. With some digging, I found an architect of substantial accomplishment in the decades before the Civil War who did much to shape the developing city. Unfortunately, his bold but unconventional choice to base his practice in Lowell rather than Boston, his birthplace, obscured his legacy. Unfairly James H. Rand is only remembered today, if at all, as the architect of the handsome but much-maligned 1855 Lowell Jail (better known locally today as the former Keith Academy; its second act and coincidentally my high school Alma Mater.) This a revised version of my original 2017 post updated with additional new research.

James Hovey Rand was indisputably Lowell’s first professional architect with a substantial body of work in Lowell, and later Boston and Maine. Despite his accomplishments and prominence in his day, his memory has largely faded but what does remain in histories and John Coolidge’s work, Mill and Mansion, is unfairly overshadowed by the controversy surrounding his most notable surviving work, the 1855 County Jail. Rand however left a legacy of design and advocacy and a broader and richer volume of work. Ironically, unbeknownst to Coolidge, Rand was the architect of what the architectural historian declared “the handsomest buildings in Lowell…”

The indomitable Kirk Boott, the multi-faceted factotum of the Boston investors who founded Lowell designed many of the city’s first structures, according to John Coolidge in his seminal 1940 book on Lowell architecture, Mill and Mansion. In fact, Boott is the only designer credited by Coolidge who ascribed the Town Hall and Saint Ann’s Church and Boott’s own imposing home to him. But Boott’s primary role in Lowell was as an engineer and business agent for the clique of Boston investors he served. Boott’s work, other than his own house and Saint Ann’s, was founded in utility and economy and informed by his military engineering training. Boott’s Lowell was a provisional, economic experiment or venture, not a full-fledged metropolis. Nonetheless, he was “The Architect of Lowell,” itself, the planner of the city. His choices, engineering, planning and economic, dictated the form and shape of Lowell and its institutions for decades to come.

The enterprising James Hovey Rand overlapped with Boott in Lowell’s second decade. Rand had come to Lowell to pursue a career primarily as an architect. Coolidge has little to say about Rand in “Mill and Mansion.” He is dismissive in his comments on Rand’s best known surviving work, the 1857 design for the Jail. “Clumsy” he fulminates, “The design is a matter of rote. The architect knew all the answers.” Had Coolidge looked more closely at Rand’s design, particularly in the context of other contemporary prisons, he might have recognized that the design was anything but rote. Rand discarded the accepted conventional prison plan of the day, and gave his jail a novel and distinctive profile, impossible to overlook. This ambitious design was an affront that his critics and political enemies would not forgive.

Coolidge is dismissive of Rand as well suggesting “He seems to have been a local person, perhaps a builder who arrogated to himself this more pretentious title [architect]” Coolidge seemed to assume that an architect outside of Boston could not be taken seriously and there were few enough of them. But Rand “arrogated” nothing; he earned his title through the accepted path in the miniscule architectural fraternity of Boston (The 1848 Boston Directory lists a total of just 21 architects.) The Jail too, seemingly unbeknownst to the historian, was the culmination of a twenty-five-year career in Lowell.

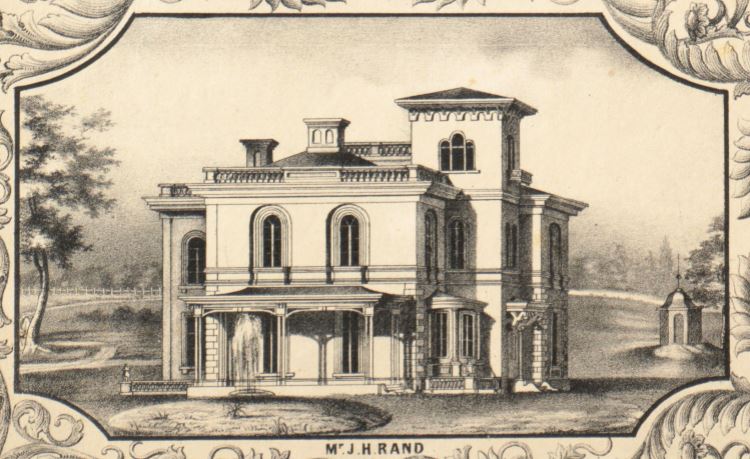

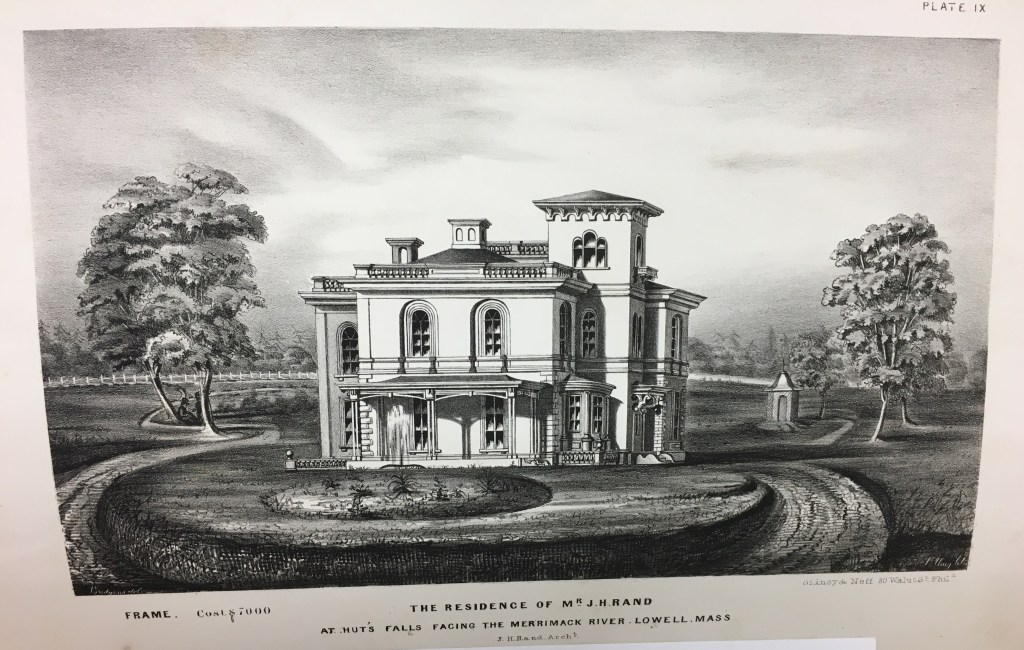

Coolidge did have restrained if qualified praise, for a grand house that Rand built for himself in 1850 calling it “The most splendid mansion of the Italian style...” His confident opinions are all the more curious because the house was destroyed decades before Coolidge’s writing and Coolidge could only have known it from small image on the margin of an illustrated map of the city prepared in 1851. Splendid perhaps but he goes on to describe it as “a ponderous structure, reflecting in its cubic form some influence from the neighboring Nesmith and Lawrence [(Butler] houses.” Coolidge’s admiration for these two works is unrestrained. “In both houses the details are of purity of form and delicacy of execution unmatched anywhere in Lowell.” He continues, “It is regrettable and significant that these two houses, perhaps the handsomest buildings in Lowell, should stand completely alone. Their designs must have seemed too subtle, too reserved to the average man of the time. Yet the influence of these two houses on the design of Rand’s own house was not coincidental for Rand was in fact the architect of all three. An 1843 account of Rand’s design for the new Nesmith House revealed as well that Rand’s design was more than “subtle” aesthetics, but technologically advanced as well. It included an early, unprecedented central heating system, just three years after steam heating was introduced into the Merrimack Corporation, along with a four-season conservatory amidst, in the spirit of Andrew Jackson Downing, two acres of gardens containing ‘‘…fruit trees, shrubs and flowers of every variety, [and] an artificial pond …” The house cost a substantial $15,000 and it was expected that Samuel Lawrence’s new house to the east would cost at least as much.

…that which attracts the most attention is the new dwelling house of John Nesmith, Esq., which occupies a fine position on the summit of the hill and commands a view of the entire city and its environs. It is a very beautiful and substantial edifice, the plan of which displays a taste and skill that gives great credit to the Architect, James H. Rand of this city…

The neighboring Lawrence House, now sadly gone, holds a particular significance in Lowell’s history, not only for its later association with Benjamin Butler or the noted influential Lawrence family but indirectly with the Lowell family as well. John Lowell, son of Francis Cabot Lowell, moved to Lowell in 1826 and was quick to recognize the natural beauty of the Hunts Falls, a rare wild stretch of the Merrimack River. He began acquiring land overlooking the scenic falls with a plan for a great country house, finding it “being the most beautiful prospect this side of the Hudson River.” The dramatic Hudson River valley was the location of many grand country seats for the New York wealthy. It was said, by a contemporary who’d seen the plans for Lowell’s house that it was modeled after “LaGrange” Lafayette’s estate outside of Paris, an ambitious project in keeping with the Hudson Valley precedents.

Unfortunately, Lowell never built his LaGrange chateau. Crushed by the death of his wife and two daughters, he fled to India where he died in 1836. Samuel Lawrence, clearly knew of Lowell’s vision and with plans of his own, acquired the Lowell lands and placed his own house, designed by Rand exactly where Lowell had anticipated his placing his own. Lawrence’s house was not on the chateau scale of LaGrange but still an imposing house of fine detailing and refined sophisticated design. It’s senseless destruction in 1980 remains unfathomable.

Samuel Lawrence himself would occupy his grand home for only few short years. His attention was focused just a year or so after its construction on an even bolder scheme: plans for the new city downriver that would bear his family’s name. In 1848 Lawrence subdivided his Lowell and Tewksbury lands and conducted a great auction, chartering a special train from Boston for bidders and catering a lavish dinner. Judging by land records, interest lagged but James Rand acquired several parcels with fine views of the falls. Even with a plan for selling out, Lawrence had insured that this seemingly natural untamed stretch of the Merrimack would be protected. The 1845 legislation incorporating the Essex Company specifically addressed the Hunts Falls.

That said dam shall not be built to float the water in said river higher that the foot of Hunt’s Falls, in the ordinary run and amount of the river.

The section continued on to establish a commission which included a representative of the Locks and Canals of Lowell, to determine and set a permanent monument for the foot of Hunts Falls as well as to determine and fix the top of the new dam in Lawrence. When after the dam’s construction, the Hunts Falls were indeed swamped, the top course of the new dam downriver was removed to restore the Falls integrity and beauty.

The influence of Rand’s Hunt’s Falls house radiated beyond Lowell. In 1844, Oliver Hastings, a Cambridge builder and lumber merchant, built himself a substantial house on Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge, another distinctive example of Regency Greek Revival. The three houses share remarkably similar massing and architectural detailing. Hastings and Rand almost certainly would have known one another in the small world of Middlesex County and through the lumber trade. Lowell, twice the size of Cambridge, was the center of a thriving timber and lumber business. The lumber wharf on the Pawtucket Canal was the depot for the Merrimack River timber runs from up-country and would have brought Hastings to Lowell. In fact, Hastings took a mortgage on a Lowell property owned by two local carpenters in 1843.

James Hovey Rand was born in Boston in 1814, the middle child of Gardner Hammond Rand, a sailmaker and Sally Frothingham; Gardner and Sally were both descended from early settlers of Charlestown. Gardner’s sail loft was in the monumental Charles Bulfinch designed India Wharf perhaps stimulating his son’s affection for architecture. India Wharf was owned by many of the same Boston businessmen who financed Lowell, including Amos Lawrence. Tragedy stalked the young family however, first with the 1815 death of James’s two-year-old, elder brother George of “worm fever,” followed by the death of “dropsy” in August of 1817 of his infant sister Abigail, and finally by the death of his father in Havana in November of that same year. How Gardner came to be in Havana is unknown. Coincidentally, Benjamin F. Butler’s father, a privateer, died on St. Kitts in the West Indies in 1819 a fact which political rivals used to try to shame Butler in the 1850s when the political and personal bonds between Rand and Butler were strongest.

Following Gardner Rand’s death, James’s mother married another sailmaker, William Scott, in 1819 but young Rand did not follow his father or stepfather into sail making but entered an apprenticeship as a housewright, serving his apprenticeship in Boston. He arrived in a booming Lowell in 1832, just after his journeyman years. An apprenticeship as a housewright in Boston was the conventional method for young men to enter the nascent profession; a housewright society supported its members with a substantial architectural library and other forms of enrichment. During Rand’s apprenticeship, for example, the architect Solomon Willard, best known for the Bunker Hill Monument, offered lectures to aspiring students. Nearly all of Boston’s architects and Rand’s peers entered the profession by this path. Where he parted from the conventional, was with his decision to establish his career in Lowell1, rather than among the small fraternity of Boston based architects.

The developing town of Lowell was the only urban place of any significance in Massachusetts outside of Boston and the ambitious eighteen-year-old must have sensed opportunities in the rapidly developing industrial center. Lowell was a phenomenon; there was nothing quite like it and it drew in the best engineering minds and the most ambitious of the day. Lowell is best known for the young women drawn to work in the mills but Rand was representative of another important migration of young New England men, mostly from upcountry New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine, all seeking financial success and opportunities to develop as tradesmen and mechanics.

Soon after arriving in Lowell, Rand joined fellow house wright Cyrus Frost as the junior partner in “Frost & Rand” located on the Lumber Wharf on the Pawtucket Canal. It was a short-lived enterprise. The pair contracted to erect a house on South Street for Cyril Coburn a lumber dealer and sometimes carpenter. All three were boarders at the widow Catherine Parker’s place on Appleton Street. Coburn had recently married Parker’s daughter Harriet. Coburn would go on to be a real estate investor and speculator; Coburn would later buy and quickly resell the prominent Merrimack House, the city’s principal hotel, in the great Locks and Canals land sell-off of 1845. Coburn and Rand would engage again in a few years in a business transaction with the Samuel Lawrence estate.

Still, Lowell was a risky choice for an aspiring architect. The profession was firmly centered in Boston. Being removed from the counting houses of State Street and the nabobs of Pemberton Square could be a disadvantage but throughout his career, Rand has business relationships with members of the Lawrence family, whose interest in Lowell coincided with the architect’s own arrival. Nonetheless to succeed would require entrepreneurship in multiple ventures and the ambitious twenty-year old started a sash and blind business as the junior partner with another housewright William Field. The exacting, detailed joinery required to craft window sash and blinds requires a high degree of skill. Rand bought the local patent rights to a new machine to simplify the manufacturing. He soon landed a contract for 2000 window blinds for the corporation boarding houses. Nonetheless, despite his many future ventures, his primary professional identification was as an “architect” as he declared his 1835 on the record of his marriage to Laurinda Moore, a dressmaker and the daughter of a farmer from Bolton in Worcester County.

His ascent in Lowell was swift. By 1836 young Rand, was running his sashworks alone and was sufficiently successful to hire house wright Joseph Buswell to build his modest first house on the corner of Fayette Street and Andover Street, the first of four houses he would build for himself, showcasing his talent and each more impressive than the last. Just five years later, 1841 he built himself a second, more substantial house on the corner of Andover Street and Harrison Street. His house may have been on the slope and not the crest, but it was in the same neighborhood as the influential and wealthy Nesmith brothers. In just two years, he would build that distinguished house for John Nesmith. This 1841 house is the only one of Rand’s four personal homes in Lowell to survive.

In 1844, following the celebrated success of the Nesmith and Lawrence houses, Rand confidently advertised his services as a design architect as well as his availability to supervise the construction of others. He’s clearly successful. An 1845 news account boasts he has offers for designs of 20 houses and it’s at this time that, he brings in Isaac Place as junior partner in the sashworks, freeing Rand to focus more on his architectural practice and his growing business interests.

Beyond simply designing their houses during the 1840s, Rand had numerous business dealings with both John Nesmith and Samuel Lawrence; it’s reasonable to assume that he produced more designs for both. Rand is the likely architect of Nesmith’s “New Block” of 1852 an Italianate style commercial building that wrapped from Merrimack Street to John Street around an earlier corner block. The Merrimack Street side has been much altered over time and split into two halves, but the John Street elevation is largely intact. It’s also possible that Rand made designs for Samuel Lawrence in his new city. Rand himself did buy one lot there on speculation. Rand designed a double house on Kirk Street for the agents of Boott Mills and the Massachusetts Mills (known more commonly as the Linus Child House.) This is perhaps not the only work he prepared for the corporations. City records indicate that during this period he designed schoolhouses and engine houses for the city along with one of the many remodeling’s of the original Kirk Boot designed Town Hall. Rand was also building modest houses on speculation including a surviving trio on Harrison Street. He was the proprietor the Mechanics Mills on Warren Street which he sold to Samuel Lawrence for expansion of the Middlesex woolen mills. He relocated the Mechanics Mills and his sashworks to Western Avenue, just beyond the Northern Depot.

John Street Elevation, Google Street View

1850 and the following decade are pivotal for Rand. In that year, he built his third house further up the slope on Andover Street, the grand Italian Villa styled house that inspired Coolidge’s measured praise. It sat proudly between its neighbors, John Nesmith’s house and the Lawrence House, now owned by Benjamin Butler. Rand’s house was destroyed in a spectacular fire 1894. There are only two know images of it, both dating from 1850. In a testimony to its prestige, the Merrimack Manufacturing Company, the most powerful of the corporations, acquired it in 1860 as a house for their Agent, perhaps the most influential figure in the city2.

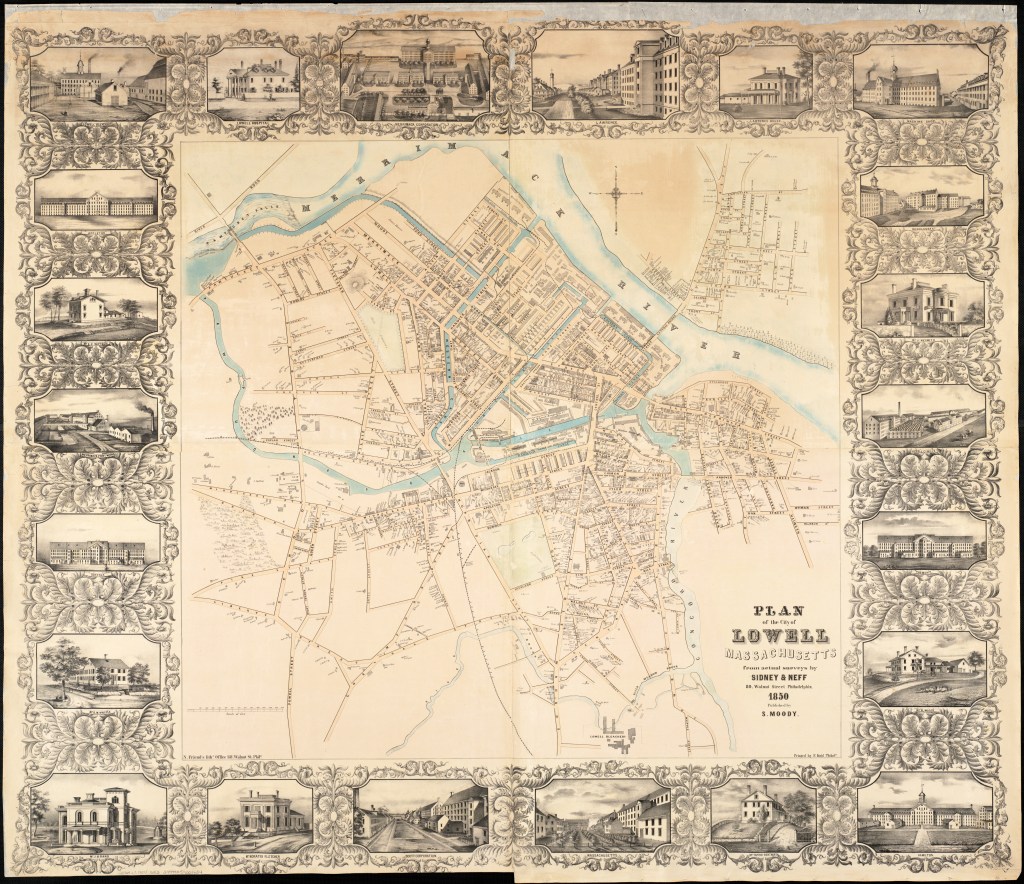

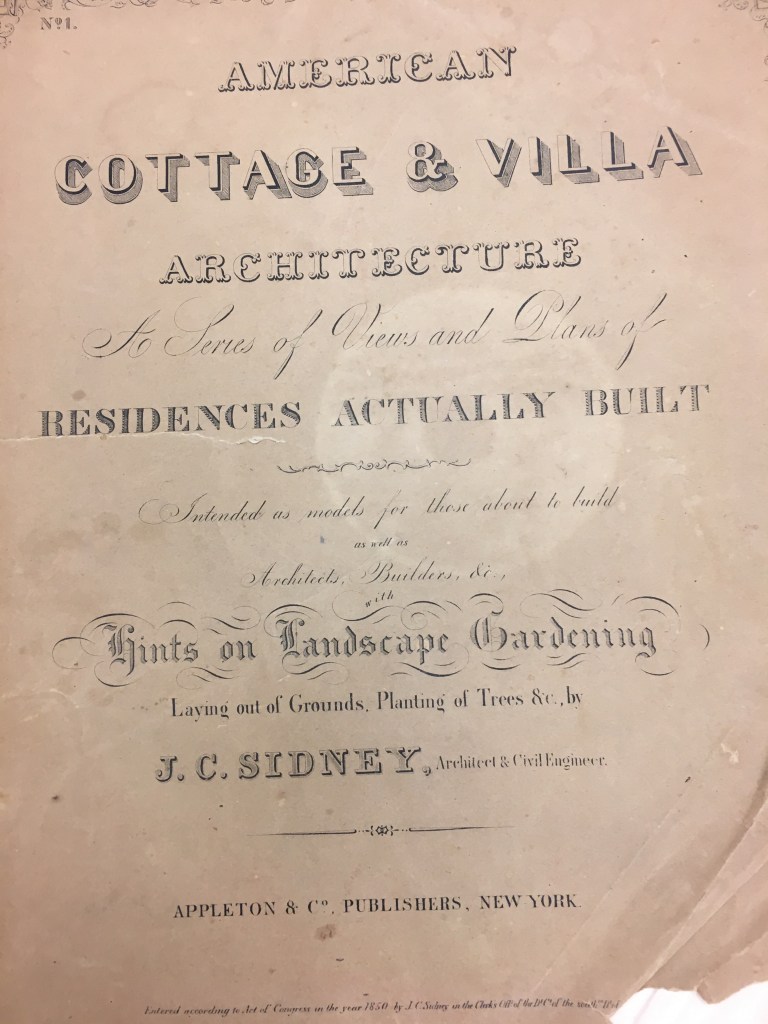

1850 was also the year that James C. Sidney, the noted Philadelphia cartographer, civil engineer and architect, along with partner James Neff, published their exceptional, illustrated map of Lowell. Sidney and Neff made a number of city maps but the Lowell example is the most distinctive. Sidney was the original designer of Philadelphia’s celebrated Fairmount Park. Rand’s house was one of the principal buildings that illuminated the map’s margins. Sidney must have been significantly impressed because he not only included it on the map but also as an example in his, American Cottage & Villa Architecture, A series of Plans and Views of RESIDENCES ACTUALLY BUILT. Intended as models for those about to build, as well as Architects, Builders, etc. It was published that same year as a subscription series. Unfortunately, there is no existing floor plan but the perspective view better demonstrates the architectural finesse that Coolidge admired and showcased Rand’s talent to a wider audience beyond Lowell. Coincidentally, the only other Boston area work illustrated was the Abbott Lawrence House in Brookline designed by Richard Bond of Roxbury.

Rand must also have had a large hand in the Sidney & Neff map and may have selected and produced the marginal illustrations. The handsome map is peculiar because while it illustrates the major corporations, absent are typical local landmarks, such as churches, schools and commercial blocks found on the other Sydney and Neff works. In truth, there were few landmarks beyond the millyards to showcase. Among the substantial mansion houses, are three coincidentally designed by Rand. It’s quite possible that Rand designed more if not all of the houses illustrated such as the Fletcher House and Moody House which share stylistic elements of his known works.

Rand’s on-going business dealings with Samuel Lawrence are hinted at in their many real estate transactions and particularly the 1844 house on Andover Street. The Lawrence House would go on to have a significant history following Samuel’s brief residency when it became the residence of General Benjamin F. Butler3.

Courtesy Peabody Essex Museum

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Rand’s entrepreneurial ventures grew. He was an incorporator of the Appleton Bank as well as the architect and part owner of the bank’s business block. The bank block was unexceptional and typical of other contemporary commercial and civic properties found around the city, simple, single gabled brick blocks with minimal architectural relief beyond a whisper of Greek Revival styling. It’s not that Rand wasn’t capable of more imaginative design; his work demonstrated his expertise and knowledge of current fashions, but in workaday Lowell, unnecessary ornamentation or novel design was ostentatious and superfluous excess. Lowell still had a provisional character; it was a place to make money, not display. Its largely transient population was ready to depart for new opportunities. As Cowley would comment, various in origin, heterogeneous in character, thrown together by chance, constantly distributing itself hither and thither, with nothing about it permanent except its changeability, – is, and always has been, grossly wanting in the municipal spirit… This same lack of attachment and a parsimonious attitude carried over to the Whig dominated city government and its spare facilities.

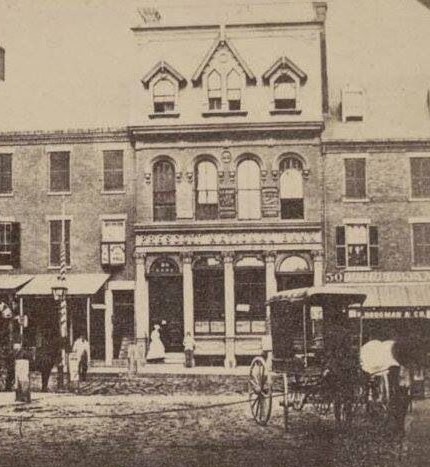

In 1851 Rand was again an incorporator of another bank, the Prescott Bank on Central Street housed in the singularly ornate and picturesque Italianate style and it stood out among its staid neighbors. The bank block also housed the Traders and Mechanics Insurance Company of which Rand was a founding director along with Rand’s architecture office. Unquestionably, a more cosmopolitan Rand was the designer, and he was transitioning to more romantic designs even if Lowell resisted. During this time, it’s known that Rand designed Lee Street Unitarian Church (the older portion of Saint Joseph’s the Worker Chapel) a rustic stone and brick Romanesque chapel. The Lee Street work bears a striking resemblance and shares many architectural features with the contemporaneous, now demolished “Grist Mill” the romantic styled hydraulics laboratory of James B. Francis of the Locks and Canals Company although that structure was designed by Edward C. Cabot of Boston, architect of the shaky Huntington Hall.

Despite his worldliness, Rand like others, could be taken in by a con. In 1847 he joined the new Houghton Association formed to investigate the story of a great unclaimed inheritance in England owed to Houghton descendants in the United States. Both he and his wife had Houghton ancestry but then seemingly, so did most of Yankee New England. When the agent hired and sent to England to investigate submitted an ambiguous report to the Directors, most were certain he was a mountebank, a grifter. Rand presumably would have an opportunity to investigate for himself, when he set off to London in 1851, but his real motivation was to see the marvel of the age, the grand Crystal Palace of the Great Exposition of 1851 He sailed to Liverpool and embarked on a four-month tour aboard the Cunard side-paddle steamer Europa.

I arrived in Liverpool the 23d of March, after a fine passage of eleven days and a half, making the run to Halifax in 26 hours and reaching Liverpool in 26 hours after touching the Irish coast.

Rand travelled in the company of several Lowell notables, including John Avery, the Agent of the Hamilton Mills, George Carleton of Carleton and Hovey, leading druggists along with the chemist, Adolphis Schlieper among others. In London, he settled in at the celebrated London Coffee House in Ludgate Hill, in the shadow of Christopher Wren’s Saint Paul’s Cathedral. The London Coffee House was a favorite of visiting Americans beginning at least with Benjamin Franklin. Rand was, as the British say, gobsmacked by what he encountered. Astonished, he reported back to the readers of the Lowell Daily Advertiser, I have been here, in London, two weeks and have made up my mind that London cannot be seen in that time. And still he reported that he’d been to the opera and five theaters over the fortnight.

If a more cultured and cosmopolitan Rand returned from his travels with an invigorated imagination, Lowell would only disappoint him. In 1852, the City of Lowell finally addressed the problem of the inadequate, too small City Hall still housed in the frequently renovated former Town Hall. The solution was novel enough: Build a shared structure with a larger city hall, a huge meeting space, atop a new depot for the Boston & Lowell Railroad. The existing City Hall building would be renovated for office uses exclusively. When the inevitable confusion ensued between the new city hall and the old Hall building, the new hall was named Huntington Hall for a former mayor. A second smaller hall was named Jackson Hall, for Patrick Jackson, the engineer, a founder of Lowell. The Whig bosses made clear that it was most definitely not named for Andrew Jackson. Like the disfavored Jackson, Rand was a Democrat along with Ben Butler. However, if the Democrats were the minority party in Lowell city, they were the majority in firm charge of Middlesex County. Rand was generally respected in both camps at least for his professional skills, but the increasing political crises of the 1850s impacted him personally.

The commission for the design of the hall and depot went to Edward C. Cabot, a fashionable young Boston architect and favorite of the Boston Brahmins. He was well connected to the Boston elite and had won acclaim for his design for the Boston Athenaeum on Beacon Street. The construction was supervised by Samuel K. Hutchinson, another Whig and a Lowell based superintendent for mill construction around the state, notably Holyoke. Hutchinson had also overseen the construction of the now forgotten Gridley Bryant designed addition to the Massachusetts State House, itself the subject of another political tug-of-war.

Cabot’s design for the hybrid hall and depot was a lumbering structure in a sort of Romanesque style then referred to as “Norman.” It lacked the elegance and stature of his Athenaeum. The finished building would be plagued with structural problems and functional inadequacies throughout its life until its destruction by fire in 1904. One terrifying and near tragic instance of its deficiencies occurred shortly after its construction. On the night of October 27, 1856, the hall was packed with a crowd of 3,000, an overflowing and enthusiastic Democratic rally assembled to hear the celebrated Rufus Choate speak. Over the stomping and cheering of the spirited throng “a jar” was heard “like the report of a canon” followed by panicked cries of “the floor is sinking!” and then ten minutes later terrifyingly it dropped again, causing a panicked rush for the doors. The center of the hall floor had indeed dropped six inches. Rand was at the rally and he and the intrepid Ben Butler went to investigate the cavity between the floor and ceiling of the depot below. Butler returned to reassure the crowd.

Colonel Butler arose, and with a calm clear voice, arrested the multitude, and telling them that the architect Mr. Rand was present and apprehended no danger.

The hall emptied and the rally continued outside. In the aftermath several newspapers around the country falsely reported that Rand had fled the hall rather than the truth that he had bravely risked his life. The Lowell Daily Courier, a Whig paper, felt it necessary to defend Rand from these outside attacks in the Boston Post.

A report having gone abroad in connection with the account of the Democratic meeting of Tuesday evening, that James H. Rand, Esq. was the architect of the New City Hall, which behaved so badly on that occasion, it is but justice to Mr. Rand to state that the report is erroneous. He was not the architect of that building, but Messr. Cabot of Boston. Mr. Rand was called upon Tuesday evening to make an examination into the condition of the hall, as an expert, and we are of the opinion that great praise is due to him for the coolness and the skill which he displayed on that occasion…the Boston Post and Courier of this morning… do gross injustice to Mr. Rand…His wife and child were in the hall at the time and he himself, while making the investigation, was in a situation of more peril than any other in the building, if the flooring had fallen through, for he was directly underneath the cracking and settling floor…We have no sympathy for Mr. Rand, politically, but simply desire to do him justice.

Investigations determined that “green” timber was used in the construction, causing it to shrink as it dried. The structural support was likely inadequate as well. Rand and others, including, James B. Francis, the Locks & Canals engineer, proposed various structural fixes and it fell to the Alderman Rand, as chairman of the City Council’s Lands and Building Committee, along with fellow members, to reassure an apprehensive public that the building would be made safe.

During the 1850s Rand’s political profile rose with his increased activity in the Democratic Party. He was selected chairman of the city’s Democratic committee and was elected to the City Council in 1856 after several prior attempts. While he held the respect of Lowell’s Whig leaders but being an ally of Ben Butler and other leading Democrats, he could not avoid enemies or politically motivated critics. His architectural ambitions, out-of-step with Lowell’s more utilitarian preferences, provided easy opportunities for criticism. In 1857 the city rejected his design for a new Myrtle Street School (Varnum School) which he’d proposed in the most modern and fashionable Italianate style. It was too expensive and frivolous. Instead, the city selected an alternative design, a customary brick barn by engineer J.W. Phillips. Coolidge, in commenting on this conservative architecture, noted the similarity of Phillip’s design to five other schoolhouses built in the prior two decades. But presumably Coolidge was unaware that Rand was the architect of at least one of these, the 1845 Branch Street schoolhouse (Franklin School,) and very likely the nearly identical Moody School of 1840 (demolished 1965.) Rand was trapped by the precedent of his own previous success.

Another source for this conservative school design was undoubtedly Henry Barnard’s 1848 design manual, “School Architecture or Contributions to the Improvement of School Houses of the United States.” which the Massachusetts legislature distributed to every city and town in 1849. Among the few design examples included was Lowell’s high school building of 1840. An architectural perspective drawing of the high school in the collection of the Lowell Historical Society presents a more ornate scheme, larger, and with considerable detailing including full articulated pilasters in contrast to the familiar, customarily muted design demonstrated in Barnard’s manual. Rand may well have been the architect of both the original and muted design in the Barnard illustration. Constraints in his creativity may have begun early.

The ultimate insult to Rand’s professional ego would be the criticism of his best remembered but most controversial design, the County Jail. Again, John Coolidge was no fan, dismissing it and its “bulging heaviness” and “insensitivity.” He was however an enthusiast of the nearby “charming” county courthouse of 1850. Coolidge did not apprehend the obvious design relationship between the two buildings. Rand’s jail and the courthouse would sit across from one another on opposite sides of the recently acquired South Common.

Modern readers may not comprehend the power of county government in 19th Century Massachusetts. Surviving counties today are vestiges of their once broad authority. The county budget was funded by assessments on the cities and towns which was often bitterly resented should the local government be controlled by the opposing party. The county budget was beyond their reach and control and so all expenditures were closely observed and excessively criticized.

The site for the courthouse was controversial from the start but the site of the future jail railroad was not. Both were selected in 1847 by the County Commissioners. The proximity of the two sites was not coincidental. The selection was deliberate and symbolic. The recent acquisition of the South Common on a highland on the southern edge of the city had also been contested. Siting these two prominent facilities on either side of the hard-won parkland was a political and aesthetic statement. The Commissioners entertained numerous locations for the courthouse but rejected the preferred location of the corporations and their proxies, a site owned by the Merrimack Manufacturing Company (the site of the today’s City Hall.) Deliberate or not, the county had created an independent civic center beyond the control of the corporations. The court house site was bitterly opposed. Local attorneys derided the location as the outskirts of the city. When the courthouse opened in 1850 the local Whig dominated bar association refused to host the customary building dedication.

If the city was miserly with its public buildings, the county was not. During these same years, the county would reconstruct the Bullfinch designed courthouse in East Cambridge, build a new Cambridge jail and replace the fire-ravaged Concord court house. All would be designed by the established Boston architect Ammi Young who would also design the Lowell courthouse. None would suffer the same criticism as the jail. At the time of the site’s purchase, Rand also had had his eye on the court design job. Apparently unsolicited, he built a model in the “Athenaeum Doric Temple” style, reflecting the much-admired design by Henry Cabot for the Boston Athenaeum. He didn’t get the job; the jail must have been offered to Rand as a consolation prize.

Young’s design for the Lowell courthouse was in the latest “Norman” (Romanesque) style and Rand would follow in complimentary fashion a few years later with his jail creating an architectural “conversation” across the South Common. Easy appreciation of the strong visual relationship between the two buildings has been obscured over the years by intervening development, particularly by a late 19th Century addition to the front of Young’s courthouse along with changes to the 1850 court house itself.

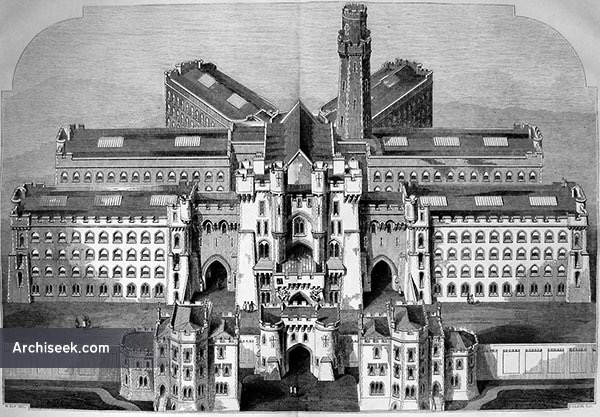

Rand was certainly influenced by Bryant’s 1851 jail. Rand’s design shares with Bryant’s, not only the monolithic natural faced granite but more pertinently the advanced humanitarian features of reformed prison design of the time including provisions for adequate light and air, hospitals rooms and separation of male and female inmates. But Rand parted from Bryant’s distinctive plan, an octagonal central tower with radiating wings. This “panopticon” design provided easy surveillance of the entire facility quickly became the paradigm for jails and prisons in eastern Massachusetts and beyond. Contemporaneous examples were built in nearby Lawrence and Dedham. The spider-like massing of these jails sits awkwardly in the setting, at odds with the street and with no readily distinguishable façade. Rand intended with his design to make an architectural statement. He pulled his jail to the street with a central gabled block and grand entry stair scaled to mirror the courthouse across the Common and to provide a proper presence on the street. He placed two substantial, conical roofed towers on each side of the central block reflecting the tower-like cupola of the court house. A separate women’s cell block to the north and a keeper’s resident to the south both linked by passageways, reinforced the primacy of the central block.

While in London a few years prior, Rand most certainly would have visited the substantial Holloway Gaol then under construction. The British were not reticent about embellishing their public buildings with substantial architecture and the Holloway Gaol enjoys a robust, romantic Gothic styling. For Lowell, despite its flourish, Rand’s jail was far more modest; American sensibilities (and pocketbooks) would not tolerate anything approaching the Holloway’s exuberance. Still, Rand’s restraint was not modest enough for his waiting critics. While they couldn’t criticize his architectural skills, they could attack his work for its presumed extravagance and there was outrage and embarrassment that now the most imposing civic structure in the city was a seemingly luxurious jail for mollycoddling miscreants.

When the Middlesex Mechanics Association held its second exhibition in September 1857, Rand, a member, entered a model of the new Jail in competition but when the award winners were announced, Rand took deep umbrage with the characterization of his work by one of the judges.

One juror, John Wright, wrote a stinging commentary:

One of the few ornamental structure of our unadorned city; affording evidence of a very creditable amount of architectural skill in its constructions and arrangement, and furnishing a safe and commodious habitation for that large and increasing class, whose energies seem mainly and assiduously exercised in securing for themselves an abiding interest in such institutions; and affording moreover on the part of those who have sanctioned the erection of that costly and imposing edifice, an example of unwise, extravagant and unjust administration of public affairs; in giving to the abode of the criminal a magnificent outside appearance and imposing on the home of frugal industry, and even struggling poverty, burden and retrenchment that crime may be cooped in a palace.

The incensed architect took the extraordinary and rare step of responding in writing over his own signature in a letter published in several Lowell newspapers. He responded:

I did not enter the new jail on the doings of the commissioners or a premium; but simply a design, plans and model of the Jail, as an architect supposing that should the Judges find my design new and useful, they would award me a diploma which would benefit me in my profession; instead, however, my contribution to the exhibition, was made an excuse, seemingly, for censuring the commissioners, deeming this opportunity to good to be lost.

Despite what was meant as an attack on the Commissioners, the claim of extravagance proved lazily persistent. Ten years later, the censorious attorney and historian Charles Cowley in his “Illustrated History of Lowell” would overstate the cost and carp of the Senseless manner in which the county commissioners wasted the people’s money on this jail…

The criticism of extravagance was baseless. A comparison of the county’s capital expenditures during the 1850s reveals that the County had spent $100,000 on the 1851 courthouse to little criticism (other than location.) A new courthouse in Cambridge cost the same and the new Cambridge jail cost $175,000. What’s more, the County’s debt was substantially reduced during this same time. A more apt comparison might be between the Lowell Jail, at a third of the size of the contemporaneous Charles Street Jail in Boston (84 beds versus 224.) At $117,000 cost the Lowell jail was far less than a third of $460,000 cost of the Boston jail. But the claim entered the realm of folklore and was repeated uncritically. Nearly a century later it may well have subtly colored Coolidge’s impressions of the jail and its beleaguered architect.

Earlier in April of 1857, in a prelude to the indignities of the Mechanics Fair, the Trustees of the Lowell Cemetery, a landscaped garden cemetery in the same tradition as the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, rejected Rand’s design for a new stone gateway because of its presumed high cost. It was estimated to cost $4500. The Committee commented that a “massive granite gateway” would not “harmonize” with the slender wooden paling that surrounded the cemetery yet acknowledging that it was the best available to the committee in the time available but that it was best to keep looking. Rival S. K. Hutchinson was invited to submit a design. Nothing resulted. But four years later in1861 the committee did select a winning design by Charles W. Panter of Brookline who would later design the 1865 gateway to the Forest Hills Cemetery in West Roxbury. The committee taking advantage of the Civil War economic troubles was able to build the design for $3100, which was then said to be one-third the conventional cost and coincidently a massive granite gateway.

Rand had been elected an Alderman in 1858, so an announcement that he was leaving Lowell that year was abrupt and unexpected and his reasons for leaving Lowell were not immediately clear. Puzzlingly, there’d even been repeated reports that he’d sought the Lowell postmaster position, although this may have been simply mischief on the part of Whig enemies. A melancholy notice in the Whig Lowell Daily Courier reflected,

Our friend, James H. Rand, has today removed from this city, which has been his home for 25 years…We are sorry to lose Mr. Rand, as he is a public spirited man, and has a warm and active heart, delighting in deeds of true charity and benevolence.

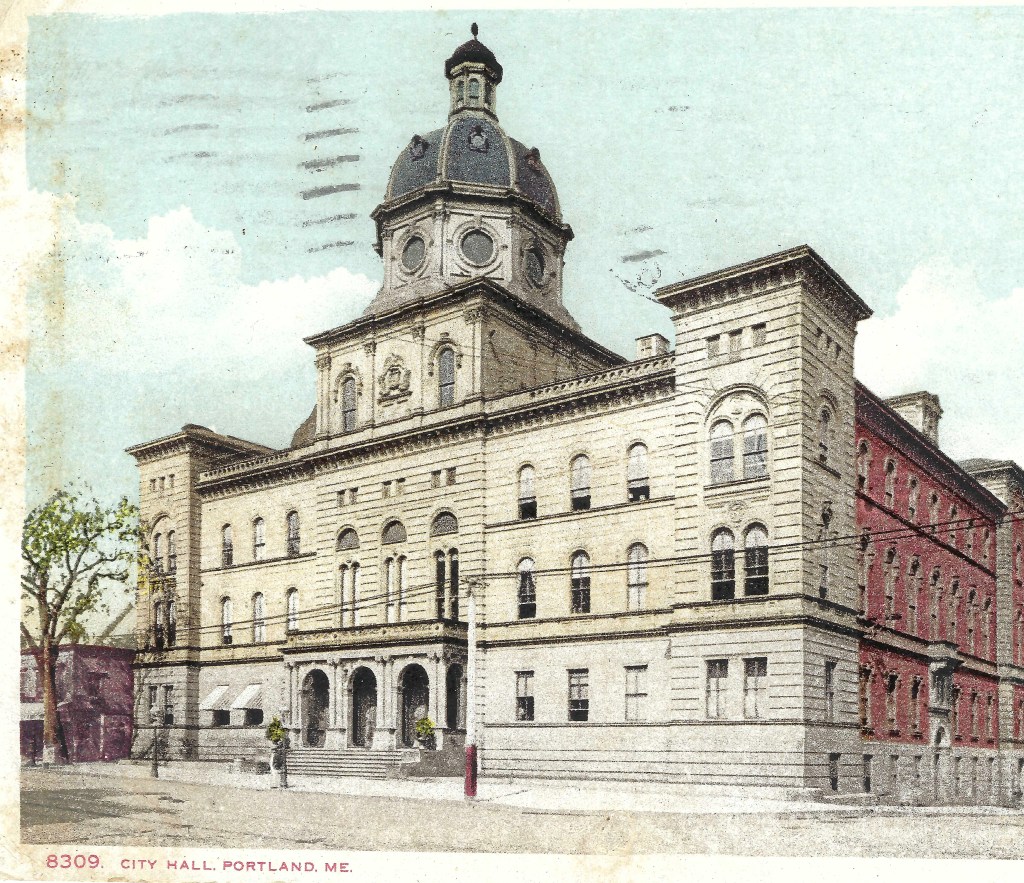

His last known local design job in that same year was for a modest but charming Italianate style schoolhouse in North Tewksbury (Ella Fleming School,) a style too dear for closed-fisted Lowell but welcome in this prosperous farming community. When it was revealed that Rand had won the design for the City Hall and Courthouse in Portland, Maine, his motivation was perhaps revealed. He must have believed that his abilities were receiving deserved attention beyond the sniping tongues of his Lowell critics. He abruptly disposed of all of his Lowell properties and returned to Boston after 25 fruitful years in the Spindle City. In Boston he shared an office with the Roxbury architect Richard Bond. With Bond’s death in 1861 Rand continued to occupy the office in the City Exchange on Devonshire Street for another ten years.

In Portland, Rand received a kind of appreciation that Lowell had seemingly denied him. This City Hall “Florentine” design was admired and received praise from Henry Ward Beecher who wrote in the New York Independent that he would have “liked to borrow it for New York or Brooklyn.” Rand also published an image of it in the premiere edition of the New York based, The Architect’s and Mechanic’s Journal.

So impressed were the Portlanders, that a 42-foot-high pyrotechnic model of the proposed City Hall was the grand finale of the fireworks display for the city’s 1858 Fourth of July commemoration. Unfortunately, the pyrotechnics proved disastrously prophetic: the finished City Hall was destroyed in the great fire of July 4th 1865; embers from a neighboring structure ignited its dome and roof. The City Hall was rebuilt using much of the surviving Rand structure but under the supervision of a local architect.

Rand would go on to design important work in Charlestown and Boston but never a project to match the stature of the Portland work or even the Lowell jail. He settled in Charlestown where he designed a school, the Warren Savings Bank and a redesign of the “Harvard” or Second Church of Charlestown along with numerous houses both there and in the growing South End and the new Back Bay along with commercial buildings in Boston and Portland; he remained politically active petitioning for the annexation of Charlestown to Boston. In a last notable controversy, when he disregarded the deed restrictions with an unorthodox facade for a house on Marlborough Street in the Back Bay in 1865, he was sued by abutters and forced to reconstruct a more compliant front.

Rand’s own third and fourth impressive Lowell houses have disappeared with his memory, He had sold his celebrated house on Andover Street in 1854 to the lumber baron Nicholas Norcross (Norcross defaulted and the house was acquired by the Merrimack Manufacturing Company in 1860.) Rand had built his fourth house in 1854 diagonally across the street; he subsequently sold it in 1857 to the manufacturer Charles B. Richmond whose misfortune is to be best known as the husband of Edgar Allan Poe’s paramour “Nancy.” This house also disappeared about 1937 and there is no known surviving image of it.

Rand appears never to have returned to Lowell until his 1883 burial in an unmarked grave in the Lowell Cemetery. The Panic of 1857 shook the city but Rand could not have known what lay ahead. The Civil War years were disastrous for Lowell due to strategic blunders by the corporations. The Panic of 1873 set back post-war recovery but by 1877 a different, more confident city was emerging. Grand homes by a new generation of local architects would join Rand’s elegant houses overlooking the Falls in Belvidere and on the slopes of the new Highlands neighborhood. Substantial new commercial buildings would follow and in the 1890s there was an explosion of imposing religious and civic buildings such as Rand and his compatriots could only have hoped to create. Rand’s 1848 Appleton Bank Block would be reconstructed in 1877 in a flamboyant Gothic Revival style by the local architect, Otis Merrill, whose firm would later design the suitably imposing City Hall of 1892, itself an object of numerous controversies.

The power of the corporations to shape Lowell’s fate may have been curtailed but not eliminated. In 1895 Joseph Ludlam, last resident of Rand’s Italian Villa and the all-powerful agent of the dominant Massachusetts Manufacturing Company declared Lowell was too expensive and that the corporation would pursue expansion in the cheaper southern states. The Merrimack mill in Huntsville, Alabama followed, signaling the beginning of Lowell’s decades-long decline.

Yet at his death in 1883, Rand was still remembered in Lowell. Still, there was that jail which would not be forgotten even it was now overshadowed by far grander public edifices. Commenting on Rand’s death, the Courier would note: [He] was for many years a well-known architect in this city and made the plans for the Lowell Jail. He also designed several of our best residences.

[1] The historian Jack Quinan, in his essay in Old Time New England, (the publication of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities aka Historic New England,) Some Aspects of the Development of the Architectural Profession in Boston Between 1800 and 1830, provides an extensive discussion and explanation of the central role of the Housewright Society to the professional development of architects and the interchangeability of the titles of “housewright” and architect. Fortuitously, the time era of his study coincides with Rand’s apprentice and journeyman years just prior to his arrival in Lowell.

[2] Following the 1894 blaze that destroyed the third house, Lowell’s then architect of record, the MIT trained Fred Stickney, was on site the following day to begin design of the replacement. He incorporated the surviving rear ell into the new house, so some fragment of Rand’s original work survived. Significantly, this new agent’s house is unlike Stickney’s other work of the period which was generally in the then popular Queen Ann and Shingle Styles. The symmetrical double bay façade, Georgian details and hipped roof would appear to make a noticeable architectural nod to the neighboring Lawrence-Butler House.

F.W. Stickney –Author

3.It’s been wrongly assumed by at least one historian that Ben Butler acquired the Samuel Lawrence House in conjunction with the 1857 collapse of the Middlesex Corporation, a financial disaster precipitated by Lawrence’s personal insolvency and the scandalous failure of his firm, Lawrence, Stone and Company. For Butler detractors, it’s yet another allegation intended to impugn the General’s character. In fact, records show that Rand purchased the house and its fourteen acres from Lawrence in 1850 at a greatly reduced price. The 1848 auction showed that there was a limited market for country villas but Rand perhaps thought otherwise. He carved out the lot for his own house and resold the Lawrence house and substantial remaining lands to Cyril Coburn, at a substantial profit, on paper at least. Coburn however defaulted on the mortgage and Rand was forced to foreclose. Butler, savvy, honestly redeemed the mortgage for two-thirds its value and acquired for himself one of the two most imposing houses of Lowell. All occurred in 1850, years before the 1857 collapse of Lawrence, Stone and Company and its victims the Middlesex Woolen Mills of Lowell and the Bay State Mills of Lawrence.