When a Revere Scandal Almost Sunk a Lowell Neighborhood

”The Death Trap”

There’s a pleasant ranch-style house on the corner of Burnham Road and Andover Street in the far reaches of Belvidere, right on the line between Lowell and Tewksbury. It’s been there for maybe 30 years; there’s nothing exceptional about it. But once, that corner was the focus of a battle between powerful local forces for the future of “Outer Belvidere.” Someone had had the audacity to try and build shops there, not once but twice, shops for which the site was legally zoned by the way. Legal or not, elegant Andover Street, as some powerful figures would ensure, would not be “despoiled” by commerce. And so for the 30 years before that house was built, the corner held a great yawning hole with the remnants of a concrete foundation, empty and abandoned. The hole was often filled with water and irresistible to curious neighborhood kids; it was what public safety types call an “attractive nuisance.” City Councilor Sam Pollard was blunter; for him it was a “death trap.”

The shops on the corner were to be the last piece of the overall development of the 35 -acre Burnham Road parcel that had begun as an innovative, low-cost veterans housing plan, only to be abandoned as collateral damage to an over-hyped rackets and bribery scandal in another city. After a several-year hiatus, the housing plan would resurface, slightly altered but to a changed environment of shifting public opinion. The urgency of the housing crisis that impelled the initial scheme had abated. The Burnham Road scheme had been one of numerous, similar developments across the state, but now the modest houses designed for an emergency drew disdain from some powerful figures determined to see that they would not be repeated here.

The initial Burnham Road housing plan was seemingly based in noble intentions. The return after World War II of hundreds of thousands of GIs, anxious to start new families, paired with the halt of construction during the war years, created a housing demand of crisis proportions. And crisis, as the old adage goes, creates opportunity, opportunity for not just the honest and creative, but also the less scrupulous. In the late 1940s, vast amounts of government money chased real and imaginary problems, with con men and opportunists trailing closely behind, eager for an easy payday. The “can-do” and improvisational attitudes of the war years carried over into impatient postwar years and many schemes surfaced, sound and not, legitimate and not. The Burnham Road project surfaced into this wary, cynical atmosphere.

A solution for Those Birth Control Houses

Lowell had hastily thrown up overcrowded temporary veterans’ housing on scattered sites around the town, built from repurposed military barracks. But this stopgap measure met only a fraction of the demand and did little to dampen growing impatience for permanent housing. Testifying at a State House hearing late in 1947, Lowell City Manager John J. Flannery derided the inadequate one-bedroom apartments as “Birth Control Houses.” Even worse, the Lilliputian-scaled, meager 289 units were hardly sufficient in the face of 1400 applications for housing already on hand. Alternatives were few for a young veteran earning $40 a week, who, as Flannery noted, couldn’t afford a $10,000 house. With this kind of urgency and the accompanying political social pressure, getting the vets and their new families into suitable and inexpensive housing quickly would require new ideas. Massachusetts legislation in ’46 and ’47 offered one solution: reduce the cost of houses for builders by having cities assume the costs of building the needed utilities and roads through low-cost, state-issued bonds. Real estate taxes on the new housing would cover the cost of the bonds. Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insurance and Veterans Administration (VA) mortgages would reduce costs for buyers. The lingering war-time mentality of massive mobilization efforts carried over in this new front. But these new tactic ran up against conservative gatekeepers like local elected officials and bureaucrats, who had little experience with massive projects, new methods of financing, or radically new construction methods and materials that challenged familiar building codes. Still, the sense of a “crisis” pressured officials to action.

In April of 1947, the state authorized a $20,000,000 program for veterans housing assistance, promising up to $5,000,000 a year in aid to the communities. The program largely targeted construction of low-cost rental housing in the state’s industrial cities, where the need was perceived to be the greatest. This new funding was promoted as the solution to the housing crisis in Massachusetts and was expected to produce 20,000 new units. Funding was largely allotted for affordable rental units to be built by local housing authorities, but the law also permitted financial support for new, low-cost, owner- occupied units.

Lowell Encounters a New Way of Building

In early 1948, Benjamin Bertram “Bert” Seigel, a Brookline-based real estate promotor, arrived in Lowell on behalf of an entity known as the American Homes Development Corporation (American Homes) with what would be a plan for 125 houses on the far eastern edge of the city. Siegel was the Roxbury-born son of a Russian immigrant tailor; he’d made his way selling Studebakers in Dorchester before the war and before graduating to real estate. Siegel’s proposal would rely on the city’s new access to bond funds to pay for the road and utility work.

American Homes was the creation of three well-known Boston attorneys and partners, Abraham Karff, Louis Hammer, and Benjamin Goldberg. The venture was a financing scheme and not the actual builder. American Homes would provide “venture funding” secured by the near total assets of the builder to the Kelly Construction Company of Arlington. It appears that American Homes was created to take advantage of the new funding and to bankroll the efforts of an established home builder to scale up operations on sites across the state and in New Hampshire. When banks, fearful of impending war with Russia, as Joseph Kelly would claim, refused financing, he turned to the less conventional source. American Homes would provide funding and also receive a fee of $200 for each home sold. American Homes and Kelly Construction would not build whole new communities on the scale of the Levittown in New York, but would rather concentrate on substantial acreage in cities and towns that could readily supply water, sewer, and gas. Cities and towns would select possible development sites to be overseen by local housing authorities. Newton was the rare example of a city that took the initiative to identify its site. Otherwise, American Homes politicked the cities to put pressure on local officials to adopt their plan and seek out the bond funds. Revere was one of the first cities to grab the opportunity in late 1947 when incoming Mayor-Elect Peter Jordan announced on Christmas Eve a plan for 417 houses, a mix of rental and ownership.

Joseph F. Kelly and his family had grown the family’s Arlington-based lumber, coal and oil business, started by his immigrant father, into a residential construction business beginning in 1939 with the Kelwyn Manor subdivision overlooking Spot Pond in Arlington. Kelwyn Manor, they boasted, was the largest FHA approved development with 100 modest homes designed by the architect Christopher C. Crowell. It also likely began the Kellys’ connections to state and Federal housing officials.

With the impending war their organization promptly pivoted to build hundreds of housing units for defense workers at sites like the shipyard in Quincy and the Navy Yard in Portsmouth. From the experience of working with these defense jobs, they developed an organization that emphasized speed and economy. They borrowed techniques from the popular house-kit sellers like Sears and precut materials offsite. And they emphasized standardization and uniformity like the Levitt Brothers. Kelly’s post-war developments resembled the Levitt developments, the massive Levittown developments in Newy York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, but built on a much smaller scale. (Kelly would later collaborate with Levitt on a 3000-house development in Puerto Rico.) The Kelly system produced uniform, modest single-story houses. It eliminated basements and simplified heating by using radiant heating in the concrete slabs. Plaster and lathe were gone, replaced with the new “drywall system” of gypsum wallboard. Houses arrived pre-cut from Kelly’s own sawmills and building elements like doors and windows were pre-assembled and ready for installation.

Today, we might describe Kelly Construction and its system as a “disrupter” overturning the existing practices and conventions of the industry. Even as he was celebrated as a housing industry visionary, Joseph Kelly would confront resistance from other builders, trade unions, and wary local officials. Kelly focused on the lower end of the market, observing in 1948 that there was a market glut of houses over $10,000, despite the overall housing shortage. He proposed that builders cede the low-cost rental segment to public housing authorities and focus on middle-class and lower-middle-class houses. He believed that government was better suited to build and run unprofitable low-income housing. Of course his preferred housing segment itself depended on by the liberal mortgage programs of the FHA and VA, which he thought should be made even more generous.

Kelly projects often met resistance. One of his first post-war developments, consisting of 100 houses in Pittsfield; begun in 1946, it ran into opposition from building trade unions as well as local builders who resented the municipal assistance he received. The community was skeptical about houses on slabs rather than foundations. In response, Kelly outmaneuvered his critics and suggested that General Electric, a major local employer, might relocate a planned expansion to another community if the Kelly scheme was not approved. High-volume building on numerous sites could be a financial risk at a time of rampant post-war inflation and serious materials shortages, but it also inspired adaptability. If one site like Pittsfield was derailed, he could move his house kits to the other communities like Leominster or Manchester, New Hampshire. When the initial Pittsfield houses came in substantially more expensive than predicted, and a federal mortgage program expired, he was forced to rent rather than sell. American Homes rescued him by buying his unsold houses and developed a plan for financing home purchases that allowed buyers to pay the down payment in installments, but response in Pittsfield was lacking.

Another development begun at the same time, ”Pinecrest Acres,” a 200-house development in Stoughton, was also offered as rentals. Renting might keep the lights on, it wouldn’t provide the capital to continue building. The expiration of the FHA program and a credit crisis caused by war fears pushed Kelly to collaborate with American Homes. Going forward, American Homes and Kelly Construction would be more closely integrated and would focus together on other ambitious projects, such as Oak Hill Park in Newton, Burnham Road in Lowell, and portentously, a 200-house development in Revere.

Garden Suburbs

Oak Hill Park in Newton was the Kellys’ most expansive project. With 412 houses on a generous 150-acre site, it was the largest single-family housing development Massachusetts to date. (The contemporaneous 789-unit Hancock Village in nearby Brookline was made up of more substantial attached, expensive rentals.) Oak Hill Park featured the same modest houses found in the other Kelly developments. But the South Newton project was conceived and driven by the city. Newton acquired and designed the site plan; Kelly built the houses. The Oak Hill Park plan was also distinct. Designed by the city engineering department and the Newton City Engineer Ashley L. Robinson, it was termed a “campus plan” and was clearly modeled after the Greenbelt towns of the New Deal Era and the Garden Suburbs movement. Clusters of houses faced onto a network of pedestrian paths free of motor vehicles, paths that lead to a village center with a school, community hall, and shopping center. Cul-de-sacs provided vehicle access to the rear of the houses. A broad curving parkway bisected the neighborhood and was to be part of a planned parkway extending from the Hammond Pond Parkway in Brookline west to Route 128. Fortunately for the neighborhood, the roadway links were never completed.

There would be no similar plan in Lowell. The 32-acre long, narrow parcel and an existing right-of-way effectively precluded it. There was no easy option besides the obvious; it would be a single, half-mile-long street. As for amenities, a small business district was allowed by zoning at the corner of Andover Street.

Just how the Burnham Road site was selected is murky, if not outright opaque. The City of Lowell hadn’t chosen it in the way Newton and Stoughton had designated their sites. In 1948, there was a good deal of undeveloped land on the periphery of Lowell, but there seemed to be no local leadership in the selection process, at least from the city government. American Homes claimed they’d undertaken a needs survey of Lowell and a comprehensive study of alternative sites, but there was no evidence that it considered other locations. The Burnham Road parcel may have had one aspect in its favor – an influential business owner fresh from a divorce and eager to sell. The American Homes study appears to have been little more than an exhibit in City Hall to market their scheme and identify potential buyers. This so-called housing “exposition” occurred in February of that year, and the actual plan became public with a March 16 City Council order directing the City Manager to begin negotiations with American Homes. It was later acknowledged that Bert Seigel, the American Homes representative, had selected Burnham Road.

The local press embraced the news enthusiastically as an important step in solving the veteran housing crisis and the development gained momentum. To aid the development, City Councilor Joseph J. Sweeney explained that the city of Lowell would take the site by eminent domain on behalf of American Homes. This was not unusual. Revere planned to sell its site to the builders at a substantial discount. Newton donated the Oak Hill site to its veterans housing board. The anxious Burnham Road property owner appeared before the Lowell City Council to support the acquisition and indicated that he was open to a negotiated sale as well. The Council had its skeptics in William Geary and James Bruin, who pushed an amendment to allow the City Manager to negotiate with other firms, but it failed when other members complained that it would delay construction. Few wanted to be the obstacle that obstruct any housing, and the proponents had skillfully exploited the sense of urgency to keep pressure up for approval. Still, curiously, the negotiations with the City Manager would drag on for several months.

The anxious property owner eager to sell was Fred S. Guggenheimer, the owner and founder of the hugely successful Scott Jewelry Company. The Richmond, Virginia native arrived in Lowell in 1934 by way of Lynn. Here, in the depths of the Great Depression, he implausibly yet brashly established the Scott Jewelry store in the heart of the downtown (his middle initial S stood for Scott.) Guggenheimer developed the idea of a credit jewelry store with generous borrowing terms. The Moderne style store, with its black Carrara glass façade and bright neon, was an island of glamorous, but attainable, luxury shining enticingly amid the circling dime stores, Woolworth’s, Kresge’s, Green’s, and Newbury’s. The business grew rapidly to nine more locations across Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and Guggenheimer was recognized as an industry leader. But in 1947, he was in the midst of a divorce from his first wife of 12 years and about to marry the “B” actress Joan Barton.

Guggenheimer had bought the land in 1944 from the estate of the recently deceased Fannie Burnham. She was recognized as a keen businesswoman who’d surprised everyone when, in 1919, she took over the management of her late father’s extensive real estate holdings. Fannie managed them with great acumen and in 1934 had been savvy enough to sell the right of way for the future Burnham Road to the city. This deftly transferred the eventual responsibility for road construction to the city, making the site that much more developable, linking her name to the site forever, and letting her pocket $500. She’d later sold a substantial portion of the future North Common Village development site to the housing authority.

Lowell hadn’t seen a private housing development of this scale- 125 houses would be built all at once-inmore than a century. As for the necessary site improvements, the city could either build them or bid the work out. Joseph Kelly of Kelly Construction, builder partner to American Homes, acknowledged under oath that an agreement with the City of Revere allowed him to walk away from the similar development there should another contractor underbid his firm. Undoubtedly he and American Homes would be looking for similar terms from Lowell.

Lowell Takes Its Time

In contrast to the parallel process in Revere, talks in Lowell were moving too slowly for the proponents – the city was deliberately cautious. After a recent contracts scandal, the city had undertaken a major reorganization of its charter, replacing an elected strong mayor with a professional “City Manager” in hopes of depoliticizing management of city affairs and eliminating opportunities for corruption. Flannery, as Lowell’s first “Plan E” city manager, had other reasons for caution as well. Seigel of American Homes had a brusque style, leading some observers to characterize him as a “hothead” and a “little Napoleon.” More significantly, Flannery must also have known that Seigel was currently under federal indictment for allegedly bribing a VA official. Flannery’s apparent wariness provoked an impatient Seigel to accuse him of being “cool” to the plan and “blocking progress.”

As for progress, there was also much skepticism from a public familiar with rushed war-time construction. Ever innovating, to speed up construction and to reduce costs, Kelly proposed a new type of untried prefabrication; the houses would be built of pre-assembled panels; Lowell’s doubtful Assistant Building Inspector Frank Cogger speculated that the houses wouldn’t meet the city’s building code. The building trade unions protested the loss of skilled local jobs. Even more surprisingly, the local AMVETS council spoke out against the scheme. Still, the City Council advanced the Lowell Housing Authority $10,000 to prepare an application to the State for the bond approval. The state housing authority provided comments on its initial review on June 5, 1948, and the comments were perplexing. Its staff had determined the site to be “low and wet with a brook running through it,” which meant the site would require draining and filling and the houses must be built without basements. It’s unclear what brook the state board found. A half century of geological survey maps didn’t show any stream, and the site’s grade dropped some 75 feet over its half-mile length to the Merrimack River’s edge. But additional filling and grading would certainly benefit any site contractor. New Englanders were chary of houses without full foundations for good reason. Still, the state board findings suited Kelly Construction; they built all their houses on slabs. Slabs not only saved foundation costs but also accommodated the new “radiant heat” system that could be cheaply installed in the slab, eliminating radiators and associated piping.

That Big Trouble in “Little Cicero”

At last, on June 15, the state authority approved the project, and the city and the developer’s representative were reportedly meeting daily to work out the final agreement. But, one month later ,the negotiations came to a dramatic halt when Bert Seigel, the American Homes representative, surrendered himself to the State Police in Revere. He was accused of being the mastermind of a scheme to bribe the Revere City Council to approve a similar housing development there. The Revere sweep would grow to 14 indictments, including five members of the City Council, the mayor’s aide, and the three principals of American Homes.

Republican Deputy Attorney General George Fingold blazed into Revere in early 1948, fresh from a rackets sweep in Fall River that landed three city councilors in jail. With an eye on the upcoming 1950 race for Attorney General, he was building his reputation as a hard-hitting “rackets buster.” Revere was an easy enough target; it was seen as was a magnet for illegal gambling and crime attracted by its racetracks and other amusements, legal and illegal. Cynical reporters, looking for an angle, labeled it “Little Cicero,” after the notorious Chicago suburb and headquarters of Al Capone, as if the beach town was straight out of the similarly cynical “B noir”movies of the day.

Lowell puts on the Brakes

In the aftershock of the Revere bombshell, Lowell City Manager Flannery announced he’d “put a hold” on the Lowell project, but it was effectively dead; it couldn’t possibly proceed with the project principals under indictment. If there was any chance of the Revere investigation extending to Lowell, distancing the city from the indicted parties now was probably a good idea. If there was any question that Lowell had abandoned the scheme, it was made clear in late 1948 when Burnham Road was briefly floated as a site for a proposed “water purification plant.” Of course that plant had even less chance of happening than the housing plan. Water pollution wasn’t seen as much of a problem and a host of practical and economic concerns doomed the plan. One opponent improbably noted that the river “has not caused a solitary case of sickness in the past forty years.” Besides, it was thought, the site was too far downstream to benefit Lowell in any way. The water would be “purified” as it exited the city. Vincent Hockmeyer, a city councilor, textile manufacturer, and Andover Street neighbor led the opposition, and the City Council killed the idea. And indeed it would be another quarter century before Lowell would begin sewage treatment at a different site up-river.

The Big Trial

Fingold’s grand jury investigation had been running none too quietly in tandem with the three months of the Lowell negotiations. During that time, it dug into all the rackets: illegal wire services, slot machines, and bribery. None of these were unique to Revere. Other cities, Lowell included, had their “jockey clubs,” and slot machines graced the back rooms of many fraternal clubs. But in Revere, it was said, mobsters brazenly shot up businesses and residences, including policemen’s houses, to discourage cooperation with Fingold. Tops among the rackets, Fingold claimed, was a $75,000 housing slush fund for widespread bribery of local officials to cement approval of one particular veterans’ housing scheme, the 200-unit plan fronted by American Homes. What’s more, Benjamin “Bert” Seigel, Fingold declared, was the “mastermind” of the whole dirty business. Seigel had indeed been active promoting the Revere development on the old Shurtleff Farm in the undeveloped north side of the city; Kelly Construction already had an option on the site. Fingold and the press sensationalized any possible angle. Even Seigel’s name was cause for suspicion for them. Was he Benjamin Seigel or Bert Seigel, they asked? (In fact he was Benjamin Bertram Seigel but he preferred to go by his nickname.) On paper, the unbuilt subdivision had a potential gross value of $1,250,000. The astronomic sum was tossed around by the prosecutors and the press suggesting that the principals might realize that fantastic payoff, overlooking the costs of construction, marketing and the like. In truth, the return on these low-cost, low- margin houses would be nothing like the big-money racket it was made out to seem, but the stratospheric number burnished the scandal.

Like its counterpart in Lowell, the Revere City Council – and specifically its Finance Committee – needed to approve the plan to land the $300,000 in bond funds needed. And as in Lowell, American Homes would be the financier and Kelly Construction the builder. The scheme reportedly had Revere buying the 65-acre parcel from Kelly Construction for $45,000 and then selling it back to them for $17,500.

So, when the Revere City Council voted eight-to-one for the American Homes plan, Fingold dropped his net and pulled in nine indictments for bribery, including five city councilors (members of the Finance Committee,) the three principals of American Homes, and Seigel. The December trial lasted three weeks with some entertainingly sensational moments. The presiding judge was the noted Felix Forte, who would be better known as the judge for the notorious Brinks Robbery trial. For this trial he cautiously ordered the jury locked up for the duration, a highly unusual move for a noncapital trial.

Fingold would attempt to show that the accused councilors had allegedly accepted substantial bribes from Seigel and American Homes, but his case rested on the dramatically embellished testimony of his star witness, the fifth indicted councilor. Young Leonard Ginsberg was a disabled war veteran and evening student at Northeastern University, who’d been convinced to turn state’s evidence against his colleagues. Fingold and state police detectives had both badgered and beguiled the seemingly naive and anxious Ginsberg who nonetheless seemed to bask in the notoriety and perhaps aggrandizing the mortal peril he believed that he faced. He darkly testified that he feared being “bumped off” opaquely continuing “…by certain parties with connections outside of Revere and certain friends of certain members of the Revere City Council [who] would …do me bodily harm.” Because of this he explained he was held in protective custody at the Andover state police barracks for three weeks. His life may or may not have been at risk, but his reputation took a hit, with some in the seaside city referring to him as “Revere’s public enemy.”

“Boys, if we go in there and vote yes, there’s $500 for each of us,” City Council President Charles S. Freeman was alleged to have said. It was also asserted that Councilor Andrew Cataldo claimed he knew of another contractor who’d pay them $5000 apiece and “build a better house.” In reply, Freeman was said to comment, “the contract has to go to the Kelly Company – it was in the bag,” but that their payments would be increased to $1000. Ginsberg regaled with a tale of a shady meeting in Councilor Freeman’s car in which he claimed Freeman said, “We already got the votes. Why don’t you come along with us? You’ll get $1000 too.” And then he described Freeman peeling $100 bills from a “roll that would choke a horse.” As for that large wad of cash, Ginsberg claimed that Freeman explained “I got to take care of the rest of the boys.” Ginsberg further testified of a trip to Manchester NH to see a Kelly housing development during which he claimed they were “wined and dined at the Manchester Country Club.” When Seigel allegedly asked Ginsberg what he thought of the Manchester house, he said he answered that “I didn’t care for it. [I] didn’t think it was worth the money.”

The accused councilors vehemently denied accepting any bribes, although Councilor Merullo admitted to taking a loan from Freeman after the vote that he was then repaying weekly. But he was reminded that he had reportedly said to detectives, “When I received the money, I didn’t want to accept it. It was a gift. So help me God, it was told to me that way.” There was even suspicion about the $7900 projected price of the Revere (and Lowell) houses , since similar Newton houses were purportedly going for $7400. This $500 discrepancy, prosecutors implied, could only be the cost of the bribes thus cheating honest veterans. Ginsberg had admitted to accepting the $1000 bribe but he undercut his own reliability when, under cross-examination, he admitted that Fingold had arranged for a job for him with a competing contractor presumably to induce him to turn state’s evidence.

In a surprise on December 9, Judge Forte ordered a directed verdict of not guilty for the three American Homes executives, the attorneys Karff, Hammer, and Goldberg. This was a rebuke for the prosecutors, even as he acknowledged “a good deal of suspicion.” The judge explained that if this were a civil case, a partner would have liability, but this was a criminal case which required a higher standard of proof; the attorney general hadn’t clearly demonstrated that the partners knew of or agreed to any bribery. The conspirators now had been reduced to five, the four city councilors and Seigel. Seigel had wisely chosen as his defense attorney the 80-year-old William H. Lewis, a widely respected trial attorney and expert on constitutional law. Lewis argued that his client and the other defendants had been denied their constitutional protection against self-incrimination, since, in those pre-Miranda Rights days, they’d all been questioned without lawyers present.

The jury was charged at last on December 18, but, after deliberating for 27 hours the foreman reported back that they were at an impasse. Forte returned them to the jury room, and three hours later they returned a verdict of not guilty for all defendants on all counts. Although the hapless Ginsberg had pled guilty to the bribery charges, Fingold subsequently declined to prosecute. Ginsberg’s admission would be held against him when the city councilors returned to their chamber and voted to direct the Revere City SoLicitor to determine whether or not Ginsberg was fit to continue serving. Ginsberg refused to step down and served out his term. In his bid for reelection, he tried to portray himself as the only principled actor who’d exposed corruption but was instead set up as the fall guy. His strategy didn’t work, and he wasn’t reelected. Bert Seigel was already under federal indictment for bribing a VA official, a charge for which he was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months (later reduced to 15 months). Seigel, in fact, probably hadn’t paid any bribe himself; he claimed he’d unwisely lent the money to a nephew, also convicted, who used it to bribe the official for a tool supply contract. Councilor Cataldo was jailed the day after the verdict for a contempt-of-court charge in another racketeering trial.

Back to the Future

Back in Lowell, the Burnham Road plan was sunk, at least for the moment. Fairly or unfairly, it would take time for the taint of scandal to dissipate. But in early 1951, over two years after the end of the Revere trial, the Kelridge Realty Trust, composed of Kelly Construction family members, bought the parcel and announced the immediate construction of 100 new homes. Joseph Kelly was seemingly the luckiest of all. The survivor of the infamous Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston,may have been designated a hostile witness but he had nonetheless survived the Revere Scandal intact (although the Revere City Council had voted to ban any future sale of the Shurtleff Farm site to him). He was back building his houses again.

The Kellys had apparently learned the hard lessons from three years earlier, and their marketing reflected it. These houses, they assured buyers, were “fully inspected and appraised by the VA and the FHWA,” had Lowell water and sewer service, and enjoyed “natural drainage [that] assures a dry lot;” There was no more talk of a suspected stream. Advertising insisted that Burnham Road offered the lowest-cost new homes in eastern Massachusetts, and in case anyone was concerned, these houses would be “built in strict compliance with the City of Lowell Building Code.” Some lots closer to Andover Street were set aside for other builders of more expensive homes.

The basic houses were small, with four rooms and just under 650 square feet, but they had generous lots of 10,000 to 15,000 square feet, which would easily accommodate alterations and additions over time. Indeed, only a handful of the houses survive today in their original form. What the houses lacked in size, they more than offset in affordability and possibilities. These were truly “starter homes” long before the term existed. But another surprise was their price; they sold for $6500, nearly 20% less than the previous American Homes plan price of $7900. But advertising didn’t feature the modest sale price; it emphasized instead the low down payment of $375. The down payment was dropped to $260 by the fall of 1951, and ads stressed the low carrying cost of $12 a week, which made home ownership appear as cheap as renting. The Kellys must have been confident, because they were simultaneously building a similar development of 23 houses in South Lowell. As for the necessary site work, the City contracted for the work for $100,000, a third of the cost estimate of 1948.

Enter the Outer Belvidere Improvement Association

Yet by 1951, the atmosphere had changed. The urgency of the housing crisis of just a few years back had abated, and the pressing need that favored speed and low cost had waned as well. Earlier skepticism now blossomed into full on disdain. The simple houses sold seemingly well but they now drew heightened scrutiny and skepticism from some influential people. The Burnham Road detractors were determined that it wouldn’t be replicated. As late as 1959, in a City Council hearing for a different housing proposal, City Councilor John J Dukeshire complained, “a developer had been allowed to build ‘chicken coops’ on Burnham Road and I don’t want to see a repetition.” The Burnham Road homeowners were understandably incensed and demanded an apology. In fact, others had already mobilized in 1952 to assure that these small houses would not be repeated. When a report surfaced of another low-cost housing development bordering the Longmeadow Golf Club, the critics quickly coalesced into the “Outer Belvidere Improvement Association.” Led by the clothing merchant Charles R. Talbot, high school administrator James Conway, and real estate and entertainment magnate Charles Dancause. The association quickly boasted a membership of more than 250. The group had two objectives, to not only control future housing developments, but also eliminate two business districts allowed under existing zoning. The Douglas Road business district existed only on paper, but a small shopping center was already permitted and under construction on the corner of Burnham Road and Andover Street when the group mobilized. The very idea of commercial uses amid the prim green lawns of Andover Street was as an abomination that would not be countenanced. Since the 1840s, Andover Street had developed as a district of wealthy country villas and later substantial rural homes for the city’s industrial elite. It had evolved into an affluent neighborhood of comfortable suburban homes on tree-shaded lots. The Improvement Association was determined to retain this status quo.

The shopping center was the final phase of the Burnham Road development. Joseph Pellegrino was the chief proponent and seemingly a worthy match for his powerful opponents. The President of the Prince Macaroni Company, the self-made Italian immigrant had built a pasta company in New York in the early years of the 20th century, lost it, and came to Boston to start over. He joined Prince Macaroni after the pasta company moved its factory to Lowell in 1939 and, under his supervision Prince became one of the major spaghetti producers in the country and a large employer in the city.

The main foe of his shopping center was another self-made man, , Charles Dancause, son of French- Canadian immigrants. For him this would be personal. His own home was in view of the new center, and he was selling house lots in his own subdivision of more conventional houses just across Andover Street. Dancause made his fortune early in automobiles. He’d secured the lucrative Chevrolet franchise for his Post Office Garage on Appleton Street. But his greatest achievement came in 1933, at the depth of the Depression, when he conjured a gleaming sports and entertainment complex from the rubble of the the abandoned and partially destroyed Prescott Mills, a baleful symbol of Lowell’s decline. From the sleek automobiles in the front showroom to the broadcast studios of the radio station WLLH, the dazzling Rex Center radiated modernity and optimism in dire times. From the literal wreckage of Lowell’s industrial past, Dancause built a promise of a revitalized city, a phoenix rising from its ashes. He grandiosely called it “The Radio City of New England.”

It may not exactly have been Rockefeller Center but Dancause, an avid outdoorsman, had created a sportsman’s dream. The Center included an auditorium for wrestling and boxing matches, a roller rink, bowling alleys, and Turkish baths. He installed a second Chevrolet dealership in a futuristic Art Moderne showroom at the front. The lunchroom quickly grew and pushed out the Chevrolets to become the Rex Café, a glamorous supper club that for the next 20 years was the leading nightspot of the town. But, by the mid-1950s, the ageing Dancause must have perceived the slow decline of the downtown and the growing migration of commerce to the city’s fringes and he was determined to block it.

The Improvement Association’s other goal, beyond stopping the “blight” of commercial development on Andover Street and Douglas Road, was to address a feared proliferation of more Burnham-Road-type developments. To make sure that Burnham Road was not replicated, they demanded not only minimum lot sizes, but also minimum footprints for one-story and two-story houses. The requirements were not excessive — 900 square feet for a one-story house and 850 per floor for a two-story structure — comparable to what was built in the Dancause lots on the opposite side of Andover Street. Of course, multiple family houses, and even two-family homes, were forbidden. The changes would not be limited to Belvidere but would extend to large areas of the Highlands and Pawtucketville on the opposite ends of the city. Kelly Construction quickly pivoted and remaining lots nearer to Andover Street were sold to another Arlington based builder, Manhattan Builders, which built more substantial and costlier homes at more than $10,000. Ads were careful to omit mention of Burnham Road featuring instead proximity to Longmeadow Golf Club.

The Improvement Association also made a fortuitous choice in legal assistance in the person of the young and promising Richard K. Donahue. Coincidently, that same year, Donahue would meet another ambitious and ascendant young man, Congressman John F. Kennedy. Appropriately enough, they made their acquaintance at the Rex Grill And Donahue would go on to become an aide to the future President Kennedy. Pellegrino and his shopping center probably didn’t stand a chance, and it didn’t help that he lived not in Lowell but in Shawsheen Village, a tony neighborhood in Andover several to the east.

But in another ironic turn, the crusade to save Andover Street unintentionally blighted the proud boulevard with the abandoned shopping center’s gaping hole and neglected concrete foundation and they would stand empty for decades. Six years after the initial battle, another leading Lowell businessman made a futile foray to build a grocery business on the desolate site. This sortie was led by Robert Lewis, a well-known and respected Lowell grocer who lived a few blocks west on Andover Street and operated the much admired ”Robert Lewis Fine Foods,” a specialty-food store in Kearney Square. He billed it “The Faneuil Hall of Lowell.” He’d opened the market just a few years earlier after many years as an executive of the once leading Brockleman Brothers Markets. In the years between the wars, Brockleman’s was a regional grocery dynamo. Its 14 downtown stores stretched from Worcester to New Hampshire, and it brought marketing excitement to the mundane chore of grocery shopping. But by the early 1950s, Brockleman’s had succumbed to the competition and convenience of spreading suburban supermarkets. Lewis believed he’d found a niche to compete with his emphasis on service and quality that even included free taxis.

Lewis, however, was looking beyond the declining downtown. The proposed market on Andover Street would be no supermarket but a “bantam” market, built in a pleasant “Colonial” motif, the better to blend with the surrounding neighborhood. But even his status as a neighbor and respected Lowell businessman could not move the guardians of the Outer Belvidere Improvement Association and Lewis failed to win the necessary zoning change. The crumbling foundation would remain neglected for another 20 years.

Ultimately the Improvement Association’s victory was pyrrhic. Even the power of the guardians of Belvidere had its limits, and one of them was the intractable town line of neighboring Tewksbury. A garish filling station had sprung up in 1955 at the intersection of River Road and Andover Street. Frank Goddard’s tractor store, just over the line, the site of a 19th-century blacksmith, was soon replaced with a drug store tauntingly named “Townline Pharmacy.” To the Improvements Association’s horror, the Garabedian farm and its homely farmstand, also right on the city line, was sold as a site for a threatened Purity Super Market. Today, it’s the location of a busy strip mall.

Charles Dancause’s Rex Center was consumed in an historic fire in 1961. The ruined site stood empty as well for nearly 20 years until it was redeveloped by Dr. An Wang, another remarkable entrepreneur who helped usher in the personal computer age and, in the process, transformed Lowell once again. The Rex site, like Lowell, seemed to resurrect itself once more. “Outer Belvidere” is simply Belvidere today, and has proved as resilient as the larger city, withstanding many perceived changes over the past half century. Burnham Road is just another of its verdant streets of comfortable homes, and that empty hole is happily long gone and seemingly forgotten. Many of the Kelly innovations have become standard practice in home building, but the focus on small, affordable houses did not survive. Kelly’s observations about where builders should focus their efforts proved prophetic as low-cost, low -income housing increasingly became the responsibility of the state and Federal governments.

William Morrissey, Commissioner of the Metropolitan District Commission presided over the dinner. Governor Paul A. Dever was on the dais, along with former Governor James Michael Curley and the indomitable Commissioner of Public Works, William F. Callahan. It was no surprise to the dinner crowd when Mayor John Hynes credited the evening’s honoree with conceiving the long-awaited public works project – finally underway – that would forever transform Boston: the Central Artery. The effort to build a highway through the center of the city had slogged on for nearly forty years, so how was it that here, among the most powerful men of the city, the credit should fall disinterestedly on an up-country dairy farmer’s daughter? Modest Elisabeth May Herlihy, daughter of Irish Famine Era immigrants, would seem an improbable candidate for this distinction, yet this evening was to commemorate the close of the remarkable career of the woman who quietly, but confidently shaped every major planning initiative of the first half of twentieth century Boston.

William Morrissey, Commissioner of the Metropolitan District Commission presided over the dinner. Governor Paul A. Dever was on the dais, along with former Governor James Michael Curley and the indomitable Commissioner of Public Works, William F. Callahan. It was no surprise to the dinner crowd when Mayor John Hynes credited the evening’s honoree with conceiving the long-awaited public works project – finally underway – that would forever transform Boston: the Central Artery. The effort to build a highway through the center of the city had slogged on for nearly forty years, so how was it that here, among the most powerful men of the city, the credit should fall disinterestedly on an up-country dairy farmer’s daughter? Modest Elisabeth May Herlihy, daughter of Irish Famine Era immigrants, would seem an improbable candidate for this distinction, yet this evening was to commemorate the close of the remarkable career of the woman who quietly, but confidently shaped every major planning initiative of the first half of twentieth century Boston.

By late 1962, William F. “Big Bill” Callahan was in a rush to finally build the Boston Extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike — and he was ready to move the Charles River, or a good portion of it, to do it. There were few obstacles, natural or political that could contain his ambition. “When we start we go. We don’t waste time.” He’d already moved the Sudbury River when it proved convenient for his plans, and the Charles would be no different.

By late 1962, William F. “Big Bill” Callahan was in a rush to finally build the Boston Extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike — and he was ready to move the Charles River, or a good portion of it, to do it. There were few obstacles, natural or political that could contain his ambition. “When we start we go. We don’t waste time.” He’d already moved the Sudbury River when it proved convenient for his plans, and the Charles would be no different.

Aerial view not to scale

Aerial view not to scale

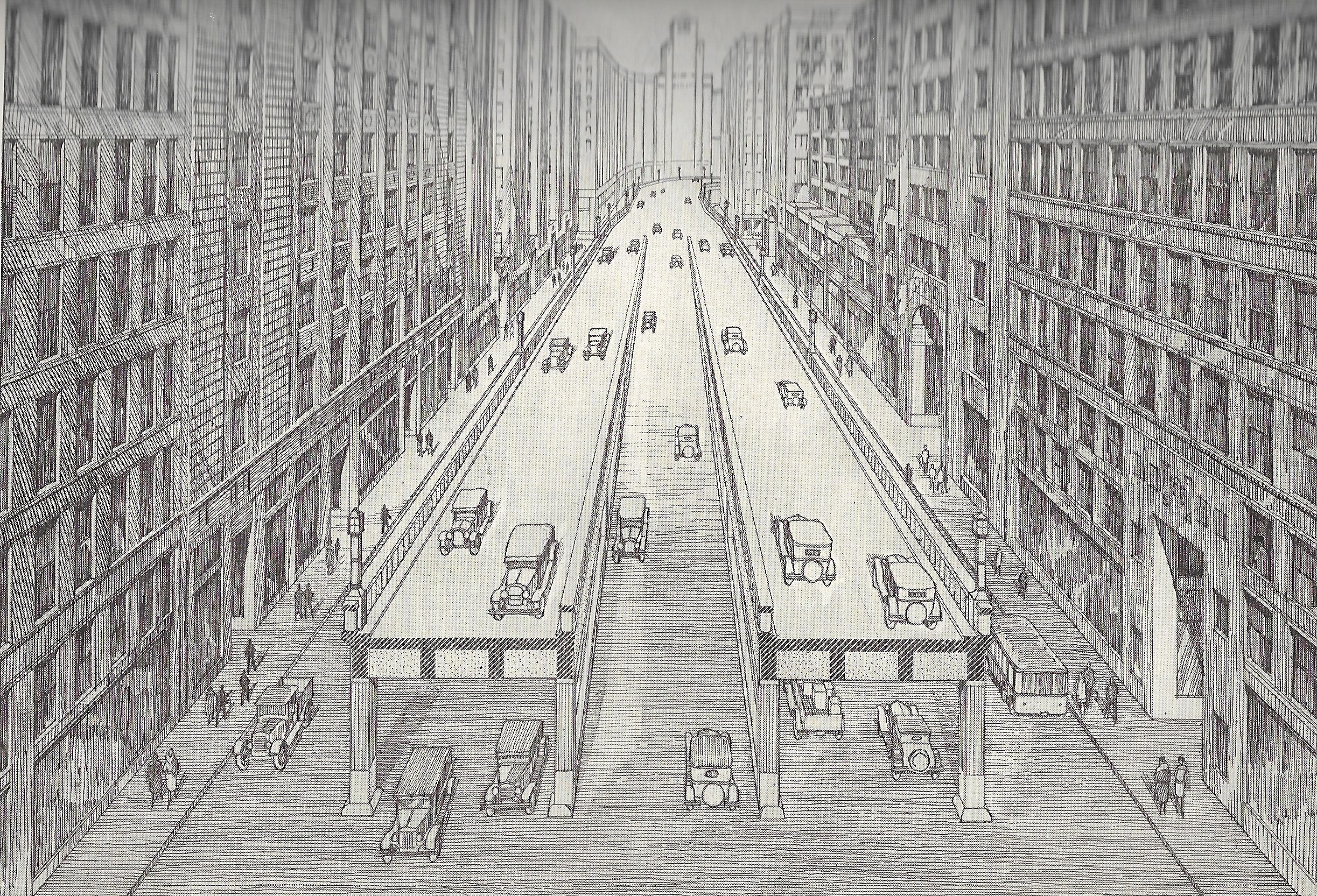

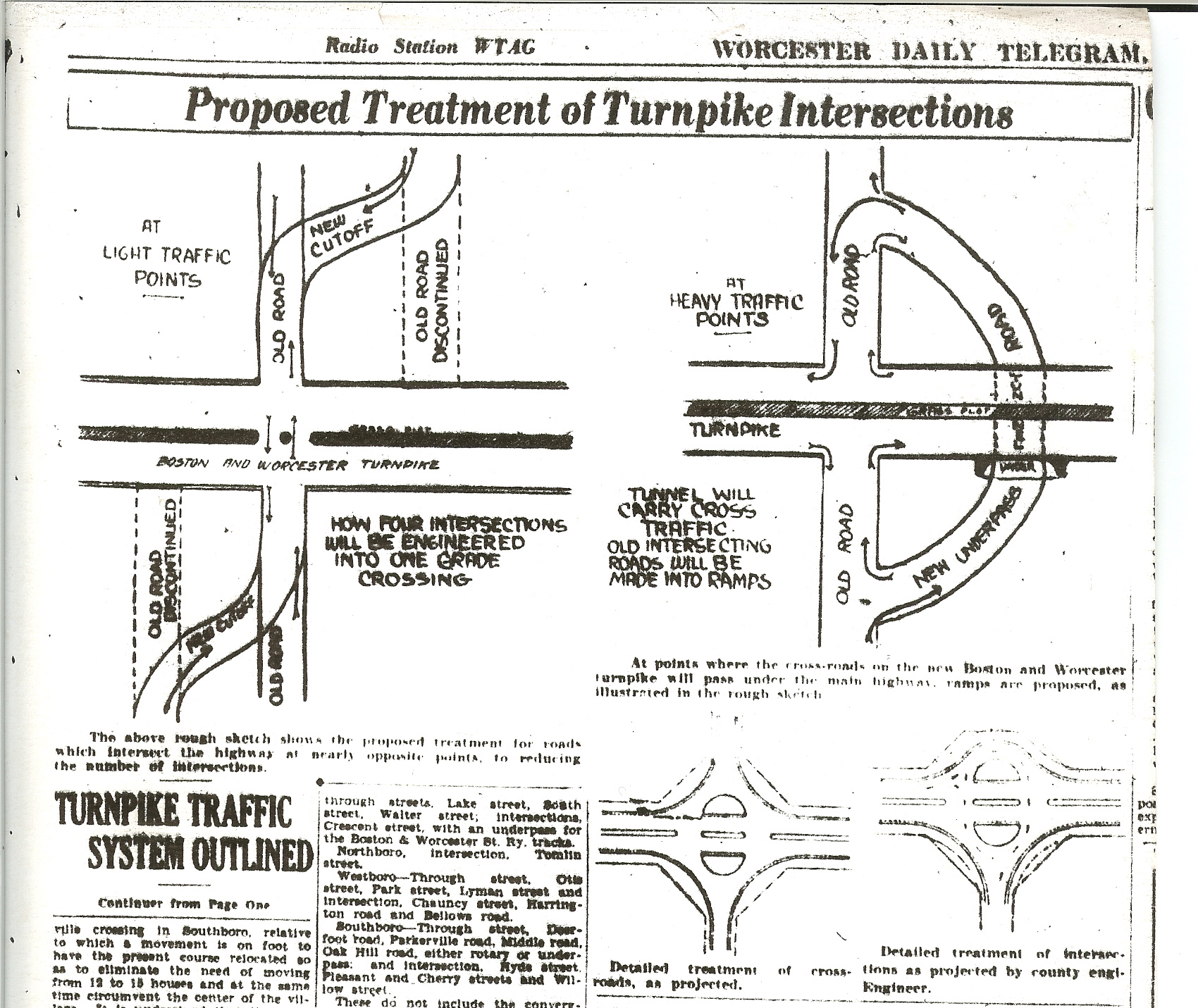

Waiting out multiple traffic light cycles in an endless queue at Eliot Street in Newton, or weaving through the mad traffic along the once heralded “Miracle Mile” of Natick and Framingham, you might find it ridiculous to imagine that the Worcester Turnpike (Route 9) was once hailed at the Finest Motor Road in the World — or even more incredibly, America’s first “Super Highway.” And yet, at the time of its construction and for several years afterward, it was the most sophisticated and technically advanced roadway of the day. It introduced many of the characteristics of the expressway that we take for granted, and it wouldn’t be equaled for nearly a decade. It initiated a new era of highway development that changed everything — construction techniques, policy, the road bureaucracy, and means of funding. Moreover, it inspired a wholesale rearrangement of the landscape of the state and its communities to create a new style of living — the expansive suburbanism of today. The comprehensive bureaucracy to plan, build, and oversee a statewide network of advanced highways would emerge with construction of the Worcester Turnpike.

Waiting out multiple traffic light cycles in an endless queue at Eliot Street in Newton, or weaving through the mad traffic along the once heralded “Miracle Mile” of Natick and Framingham, you might find it ridiculous to imagine that the Worcester Turnpike (Route 9) was once hailed at the Finest Motor Road in the World — or even more incredibly, America’s first “Super Highway.” And yet, at the time of its construction and for several years afterward, it was the most sophisticated and technically advanced roadway of the day. It introduced many of the characteristics of the expressway that we take for granted, and it wouldn’t be equaled for nearly a decade. It initiated a new era of highway development that changed everything — construction techniques, policy, the road bureaucracy, and means of funding. Moreover, it inspired a wholesale rearrangement of the landscape of the state and its communities to create a new style of living — the expansive suburbanism of today. The comprehensive bureaucracy to plan, build, and oversee a statewide network of advanced highways would emerge with construction of the Worcester Turnpike.

Brookline’s opposition was pecuniary rather than aesthetic, since the town was to be responsible for a large portion of the cost of the road, which Chairman of the Board of Selectmen Charles F. Rowley fumed was “…an example of extravagant public expenditure.” “One would assume that every vehicle travelling upon the road was tearing madly between Boston and Worcester …The great majority of the vehicles … are pleasure vehicles… which will in no way be financially affected [by] arriving three or four minutes later at their destination.” Brookline’s plan saved two-thirds of the cost of the state’s proposal. It also didn’t hurt that it would spare the Longwood Cricket Club and the now-defunct Chestnut Hill Golf Club.

Brookline’s opposition was pecuniary rather than aesthetic, since the town was to be responsible for a large portion of the cost of the road, which Chairman of the Board of Selectmen Charles F. Rowley fumed was “…an example of extravagant public expenditure.” “One would assume that every vehicle travelling upon the road was tearing madly between Boston and Worcester …The great majority of the vehicles … are pleasure vehicles… which will in no way be financially affected [by] arriving three or four minutes later at their destination.” Brookline’s plan saved two-thirds of the cost of the state’s proposal. It also didn’t hurt that it would spare the Longwood Cricket Club and the now-defunct Chestnut Hill Golf Club.

More controversy would follow construction, when the roadway between Framingham and Brookline started deteriorating almost immediately. It was suggested that the resulting cratering was caused by calcium chloride de-icing. A $20,000 study by Charles Breed of MIT was commissioned and its results then suppressed for eight years. When the study was finally made public, it revealed that the real problem was construction deficiencies cause by poor oversight and missing and poor quality concrete.

More controversy would follow construction, when the roadway between Framingham and Brookline started deteriorating almost immediately. It was suggested that the resulting cratering was caused by calcium chloride de-icing. A $20,000 study by Charles Breed of MIT was commissioned and its results then suppressed for eight years. When the study was finally made public, it revealed that the real problem was construction deficiencies cause by poor oversight and missing and poor quality concrete.