It was a seasonably mild spring evening in 1950 with a touch of rain, but not enough to dampen the spirits of the 300 of Boston’s civic, political and business leaders gathered for a grand testimonial dinner at the elegant Copley Plaza Ballroom. They’d assembled to commemorate the retirement of one of the most influential figures in Boston. This kind of grand, testimonial dinner seems particularly anachronistic these days, but then it was a genuine expression of admiration and affection for a singularly accomplished person who had quietly guided the city and the region’s planning and development for the past thirty-five years. William Morrissey, Commissioner of the Metropolitan District Commission presided over the dinner. Governor Paul A. Dever was on the dais, along with former Governor James Michael Curley and the indomitable Commissioner of Public Works, William F. Callahan. It was no surprise to the dinner crowd when Mayor John Hynes credited the evening’s honoree with conceiving the long-awaited public works project – finally underway – that would forever transform Boston: the Central Artery. The effort to build a highway through the center of the city had slogged on for nearly forty years, so how was it that here, among the most powerful men of the city, the credit should fall disinterestedly on an up-country dairy farmer’s daughter? Modest Elisabeth May Herlihy, daughter of Irish Famine Era immigrants, would seem an improbable candidate for this distinction, yet this evening was to commemorate the close of the remarkable career of the woman who quietly, but confidently shaped every major planning initiative of the first half of twentieth century Boston.

William Morrissey, Commissioner of the Metropolitan District Commission presided over the dinner. Governor Paul A. Dever was on the dais, along with former Governor James Michael Curley and the indomitable Commissioner of Public Works, William F. Callahan. It was no surprise to the dinner crowd when Mayor John Hynes credited the evening’s honoree with conceiving the long-awaited public works project – finally underway – that would forever transform Boston: the Central Artery. The effort to build a highway through the center of the city had slogged on for nearly forty years, so how was it that here, among the most powerful men of the city, the credit should fall disinterestedly on an up-country dairy farmer’s daughter? Modest Elisabeth May Herlihy, daughter of Irish Famine Era immigrants, would seem an improbable candidate for this distinction, yet this evening was to commemorate the close of the remarkable career of the woman who quietly, but confidently shaped every major planning initiative of the first half of twentieth century Boston.

By the early twentieth century, the art of American city planning was aspiring to a science; it had broadened from the great aesthetic impulses of the “City Beautiful” movement of Charles Burnham and his peers to encompass the determined reformers, generally upper-class, of the “Good Government” movement, disparaged by populists as elitist “goo-goos.” These were urban and social reformers with a moral certitude that the most vexing problems could be solved, and the under-classes raised, not by aesthetics but through impartial scientific observation and analysis in pursuit of clean water, sanitary sewerage, decent housing, better education, and relief from dense, congested conditions. For them, the disadvantaged were victims of their physical environment. Correct those deleterious conditions, as often as not, by grand public works or renewal schemes and a good bit of secular evangelical zeal and the uplift would follow. As Herlihy herself would write in the periodical The American City in 1919: “People cannot be compelled to live rightly until right living conditions are available.”

The young Herlihy came from far different circumstances than the typically aristocratic reformers when Mayor John F. Fitzgerald appointed her Secretary of the first Boston Planning Board in 1914. She was not born in Brookline or Wellesley, but in Wilton, New Hampshire, the youngest of eleven children of John Herlihy and Catherine Hannon. Perhaps ambition runs in the family. Her parents, he from Cork and she from Limerick, were married a year after John bought the first of three farms he would own in Wilton, a singular accomplishment for a young immigrant. Her older brother Charles studied, first in Lowell and then the law in Boston, and with his brother Joseph established a major milk distribution network. But Elisabeth would eclipse her older siblings’ accomplishments if not their wealth. After studying at Bryant & Stratton Business College in Boston, she established herself as a public stenographer, a position which brought her in contact with leading business and civic figures. Following the election of John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald as Mayor of Boston in 1910, she began working for the city as a clerk, and within a few years she rose to chief clerk and ultimately the new Board’s Secretary.

The distinguished architect, Ralph Adams Cram, was the first Chairman of the Planning Board. Those first years of the Board must have been a master class for Herlihy, and an equal and possibly greater influence undoubtedly came from Board member Professor Emily G. Balch, head of the Economics Department of Wellesley College. As Secretary, Herlihy was a shrewd choice. She provided a gentle buffer and intermediary between the sharp elbows of gritty ward politics and the fervor of the reformers. She spoke the languages of both worlds. In later years as a lecturer to students or civic groups she would advise her listeners to embrace, not shun, politics as the vehicle to accomplish reform. One politician who would prove crucial to her career would be James Michael Curley and she cheerfully returned the esteem writing speeches and thanking him for his support.

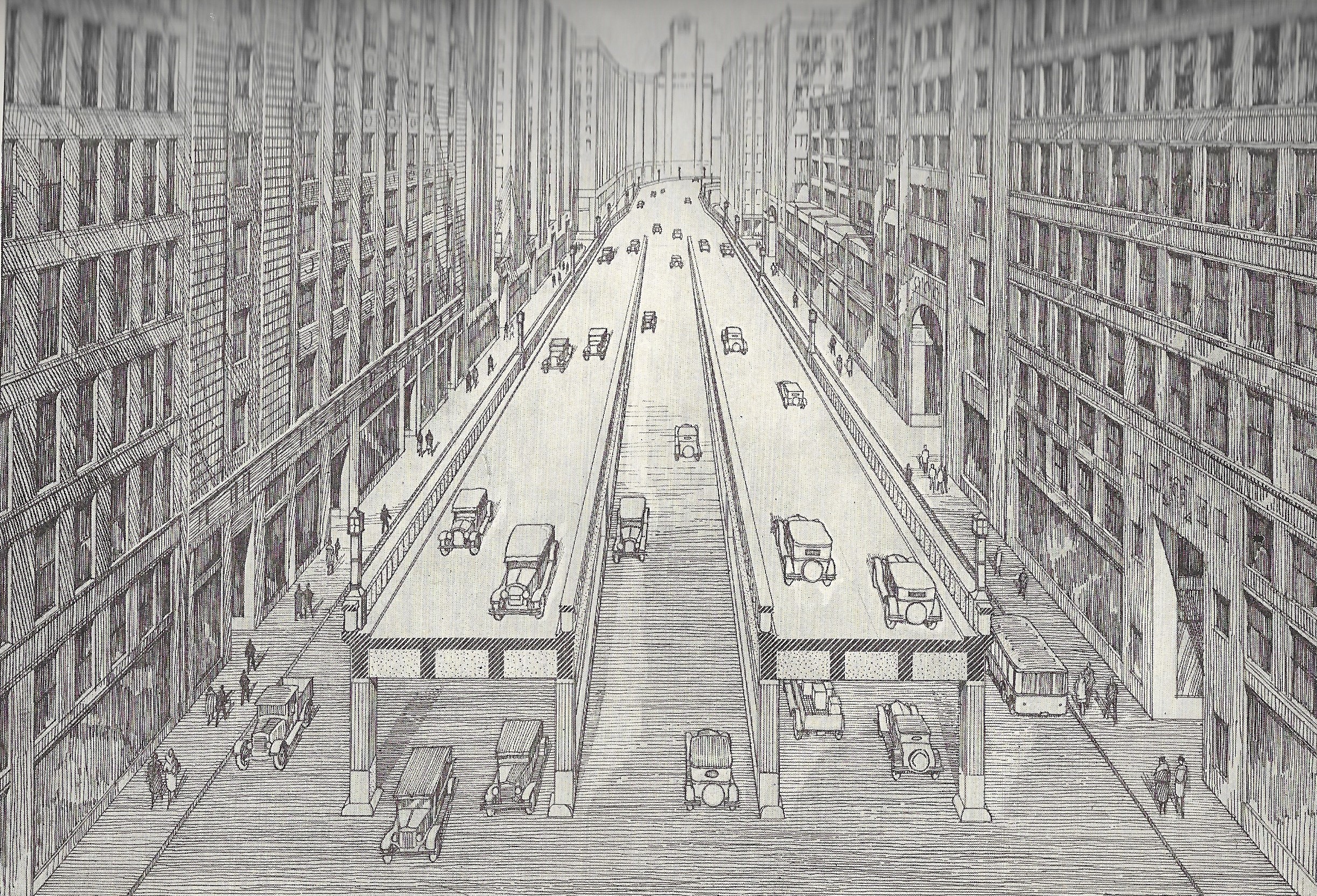

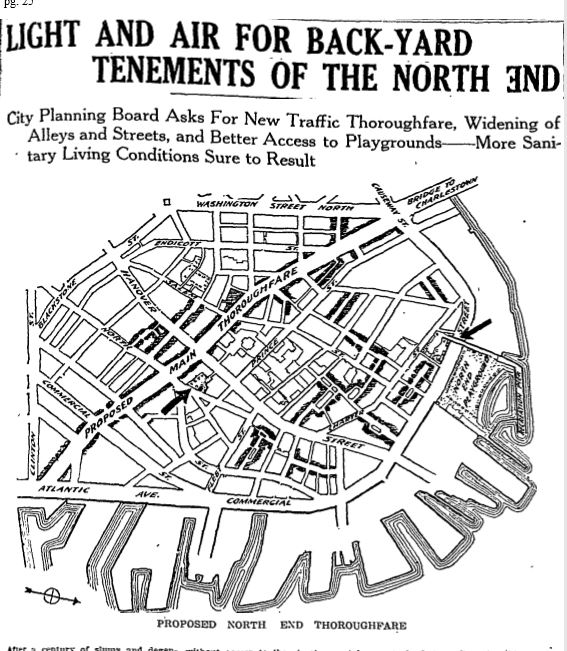

For reformers, Boston’s narrow, discontinuous, and congested streets were complicit in the degraded living conditions of the poorest citizens. “Right living conditions” would require congestion relief, primarily through roadways widening and realignment. Thus in 1918, taking up the cause of the reformist “Boston 1915” movement the nascent Planning Board presented an ambitious plan to address the dense conditions of the North End. The Board focused on a perceived lack of light, air, and playground spaces. The North End, not unlike other neighborhoods, had grown denser over the previous century with infill structures. Razing them, widening streets, and creating green spaces and playgrounds would bring welcome and uplifting change. But by far the most ambitious (and costly) element of the plan was a new cross-town street, the “Main Thoroughfare,” which would run across the North End from Atlantic Avenue to the Washington Street Bridge.

Boston Globe 12-12-1918

The thoroughfare was less ambitious than the one recommended by the Joint Board for Metropolitan Improvements in 1911, (which essentially followed the route of the modern Central Artery but included a rail tunnel beneath to link North and South Stations.) The 1911 plan failed on cost, despite the New Haven Railroad’s pledge to pay for the tunnel. The1918 proposal ran exclusively through the North End and was to be located further east, between higher-value and lower-value real estate, and the combined impact of the new roadway and the clearance efforts would undoubtedly pay for the improvements by increased valuations and resulting taxes. The thoroughfare was part of a larger scheme that included numerous other roadway widening intended to transform the North End. It was suggested that the new road be named for the Marquis de Lafayette, but despite the French name, the proposed road, with its many crossings, lacked the clarity and elegance of one of Baron Haussmann’s Paris boulevards or the power of an Emperor to make it happen. It too would fail, although various North End improvements did take place.

By 1923, just seven years after her appointment, a determined Herlihy had become a recognized planning authority, and she led Boston through the adoption of its first comprehensive zoning ordinance. She was an observant Roman Catholic, and some of the evangelical zeal of the reformers can be found in her explanation of the need for zoning. “Order is Heaven’s first law, and zoning is but an attempt to bring about order in civic development,” as she explained to a reporter for the Sunday Advertiser. An earlier zoning effort 1905 was a reactionary effort limited to regulating building heights, but this new plan would be more comprehensive, regulating uses and density of structures. When William J. McDonald, the influential developer of the Park Square District and a Curley supporter, lambasted the height cap as a drag on growth, the limit was increased from 125 feet to 155 feet. Heaven’s order could be consistent with political necessities.

Herlihy’s sense of order looked beyond Boston. When asked by a Boston Evening Traveler reporter in 1923 for her predictions for 1930 she answered:

My first hope is that by 1930 the forty cities and towns comprised in the Metropolitan District may have outgrown local prejudices and conservatism, and become banded together under a centralized form of government as a metropolitan Boston… <with> a comprehensive plan covering the entire district… <for> the preservation of order and beauty in the physical growth of the entire region.

She gained a new ally toward this vision that same year, when the Legislature created a Division of Metropolitan Planning within the new Metropolitan District Commission, with Henry I Harriman of the Boston Chamber of Commerce as its chairman. The Division was responsible for the study, planning, and recommendation of potential transportation improvements, both road and rail, for the entire Metropolitan District.

The unprecedented surge in private autos only aggravated existing congestion and inspired searches for new fixes. The previous idea of a grand boulevard to ease traffic between the rail terminals and the wholesale markets resurfaced. In February 1925, the Legislature created a special recess commission that included Harriman and Frederick Fay, then Chairman of the Boston Planning Board. The commission recommended an “interim thoroughfare” with two segments, but by March the proposal had morphed into the “Loop Highway,” a broad thoroughfare running from Kneeland Street across Haymarket and linking up at the Charles River Dam to the newly built “Northern Artery” which ran through Cambridge and Somerville. Cost estimates ranged from $33,000,000 to $50,000,000. Not everyone thought that a new roadway was necessary. Opponents, led by Representative Henry Shattuck, powerful chairman of Ways and Means, imagined that congestion could be solved by banning on-street parking, if not completely, at least before 10AM, since arriving commuters and shoppers in search of on-street parking certainly compounded the traffic problem. Why, they asked, should the city surrender this valuable real estate to all-day parkers? Shattuck also believed that the cost of a roadway would be better spent on extending the subways. The powerful legislator Martin Lomasney, the “Mahatma of the West End,” was certain that this was a scheme to benefit rich real estate speculators and his opposition insured death of the plan in April of that year. But before the project was killed the New York traffic engineer Henry M. Brinckerhoff suggested an intriguing idea to place the roadway on an overpass above Haymarket Square. New roadway proposals to follow would now take to the air.

Early 1927 brought another attempt, this time an ambitious all-elevated highway that would run from the Cottage Farm Bridge (today’s BU Bridge) along the Boston and Albany tracks to South Station, where the Atlantic Avenue Elevated train structure would be repurposed as a highway to North Station terminating as before at the Charles River Dam. The necessary legislation failed yet again due in no small measure to the opposition of Martin Lomasney.

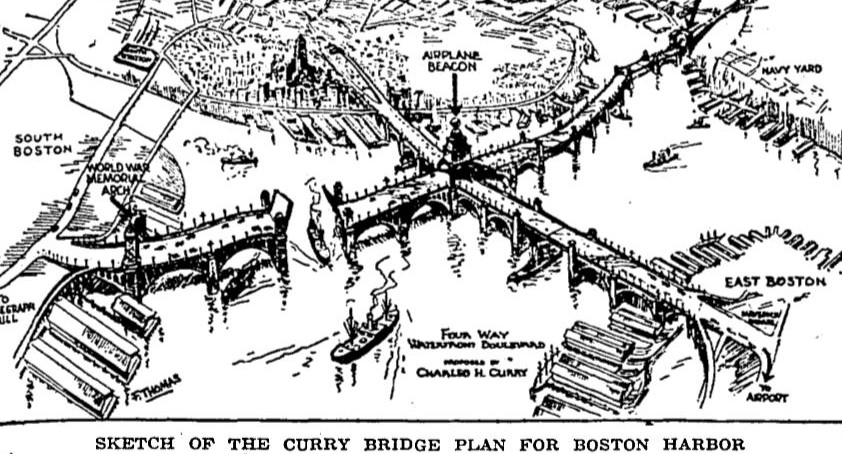

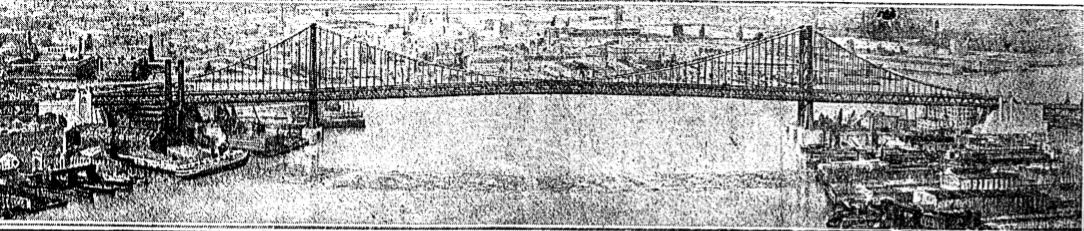

In 1929, a new idea came out of left field, when Boston businessman Charles Curry proposed a spectacular bridge from South Boston to Charlestown across the harbor, eliminating the road through the city. The plan included a second bridge from downtown to East Boston, and the two would intersect under an Eifel Tower like “aeroplane beacon.” It was preposterous, but the East Boston bridge, not a new idea, had caught the interest of some powerful supporters particularly Mayor Curley. In fact, in 1926, the Metropolitan Planning Division had proposed a more realistic yet still dramatic suspension bridge along with a practical tunnel alternative. Curley was convinced that a bridge would allow him to drop the ferries which were an expensive liability for the city; his opinion would shadow all future proposals.

Boston Globe 11-29-1929

Division of Metropolitan Planning 1926 East Boston Bridge Proposal

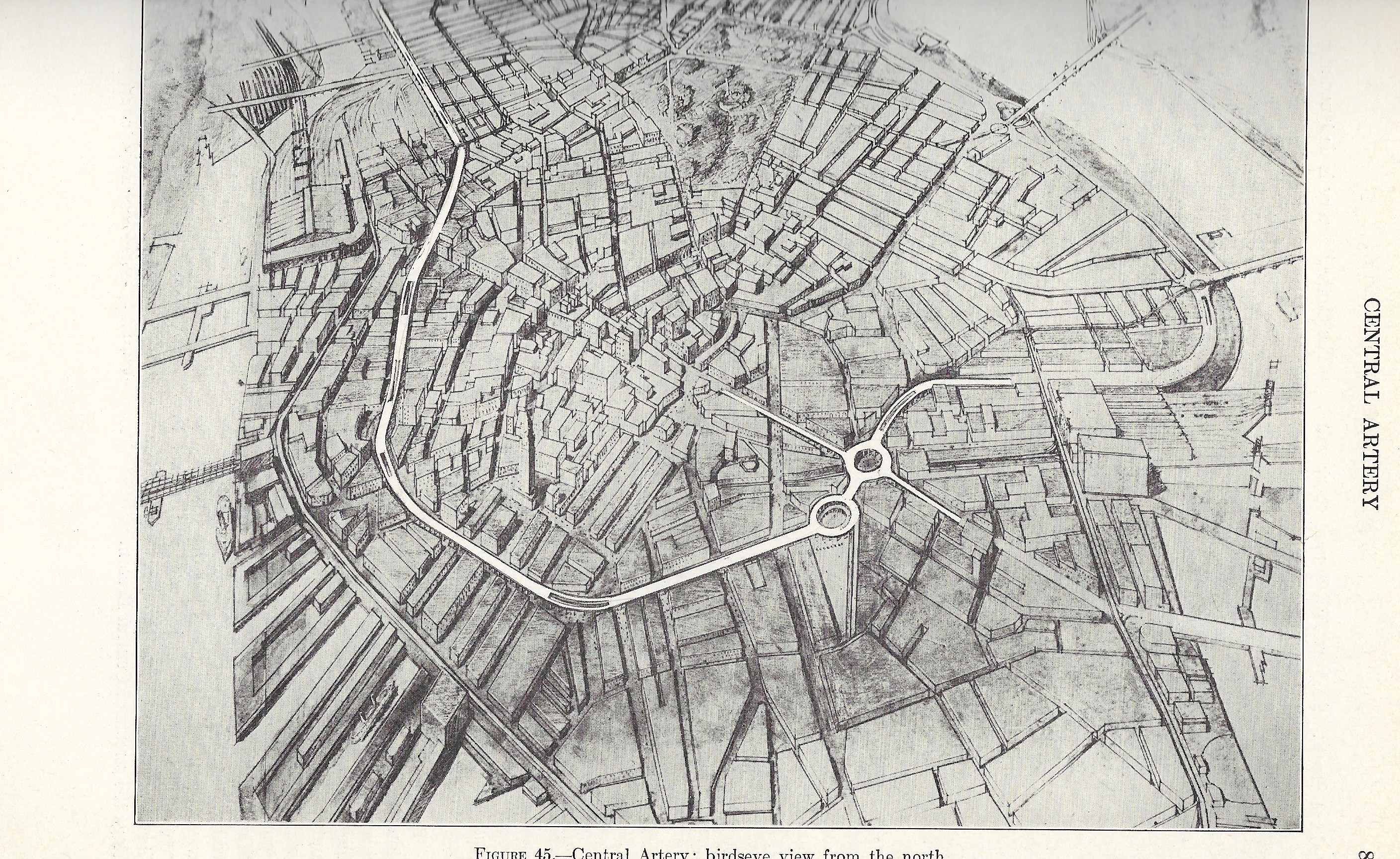

Metropolitan Planning and the city Planning Board in 1928 again filed legislation for a more modest elevated highway which yet again failed but this elevated highway introduced the new term “Central Artery.” This Artery would form the core recommendation of the ground-breaking “Report on a Thoroughfare Plan for Boston,” an unprecedented, comprehensive city-wide, thirty-five-year highway plan. Proposed roads terminated tantalizingly at the city limits, because a companion metropolitan plan had been quashed.

Central Artery. Thoroughfare Plan 1930

Often referred to as the “Whitten Plan” after Robert Whitten, the planning consultant who assisted the plan however it was largely the work of the Boston Planning Board’s staff. Elisabeth Herlihy officially contributed only a chapter on the history of Boston’s streets, but her influence is apparent throughout the plan. Its recommendations were developed from actual traffic counts and observed traffic corridors identified through origin-and-destination studies analyzing drivers’ habits. The plan was what we might today call a data-based plan. It was meant to be a solid, pragmatically engineered rationale for a major roadway program with a twenty-five-year construction schedule. It even included traffic estimates and flows for 1965 -, thirty-five years into the future – which were, in hindsight, grossly underestimated. And although most experts favored a tunnel, Herlihy wisely proposed a tunnel or bridge alternative for East Boston.

The arrival of the plan at the beginning of the Depression should have been propitious. Governor Ely and the Legislature would shortly initiate an unheard-of “superhighway” program for Depression relief that would include the futuristic Worcester Turnpike (Route 9), the Southern Circumferential Highway (Route 128), and the Providence Turnpike (U.S. Route 1.) But when the vast construction program bogged down in controversy and failed to deliver the hoped for economic boost, Ely and the legislature abandoned further work. Large-scale highway construction through the rest of the ‘30s would languish until the arrival of the Federal WPA funded program. Up until the Depression, roadway funding in Massachusetts, with few exceptions, had been “pay-as-you-go” and the Legislature held wide-ranging control over Boston’s budget and debt. Thus the Legislature, leery of Curley and debt averse, authorized only $3,500,000 of the $31,000,000 he’d requested for his ambitious “thoroughfare plan.” Curley’s bridge proposal too would fall in the face of opposition from the War Department. The tunnel would be built instead but ironically it would be a financial albatross for Boston for most of the ‘30s.

Curley succeeded his intra-party Democratic rival Ely as Governor in 1935. He established a State Planning Board in 1936 in compliance with the Federal Works Progress Administration, and he turned to his long-standing ally Elisabeth Herlihy to head it. From this new position as the state’s leading planning expert, she would oversee coordination of planning efforts across the state. Her staff, swelled by WPA workers, developed detailed statistical profiles of Massachusetts cities and industries to help ensure eligibility for the Federal aid. She would be pivotal in flood protection plans along the Connecticut River following the disasterous hurricane of 1936, staring down the recalcitrant governors of Vermont and New Hampshire, and she would continue to be intimately involved with highway planning with a statewide plan in 1937 and worked with Mayor Tobin of Boston in 1940 for a yet-again revived Central Artery.

It was in the post war period however that Herlihy made some of her most important contributions to the effort to build the Central Artery. In 1947 the State Planning Board, in conjunction with the Department of Public Works, put together yet another comprehensive plan for roadway construction in Metropolitan Boston. It was commonly called the “Duffy Plan,” after Harold Duffy, the State Planning Board engineer who developed it. But the Duffy Plan ran into critical opposition from Mayor Curley, who favored a competing scheme of a waterfront artery and, yet again, that bridge to East Boston.

The competing bridge plan was proposed by the real estate investor William J. McDonald, a long-time Curley supporter. Senator Staves, the powerful Southbridge Republican chairman of the Highways Committee, was eager for a comprehensive highway program and urged Mayor Curley to find a compromise. Curley called a luncheon conference at the Copley Plaza hotel where Herlihy, a key member of the committee, undoubtedly influenced her old friend Curley to back a new compromise plan that included a second harbor tunnel rather than a bridge.

In late 1947 a group including Herlihy and led by Senator Bowker of Brookline, travelled to New York to consult the great highway oracle, Robert Moses. “Moses is taking a deep interest in Boston’s problems,” Bowker reported eagerly. Herlihy commented politely on Moses’s “information” and “cordiality” and while Moses was a proponent of bridges over tunnels, Herlihy subtly checked his influence through an unassuming comment that ‘[he] would not like to advise on the Boston situation until he had studied local conditions.” It appears that he indeed never did. She commented that Moses “he has not much faith in origin and destinations surveys,” but she pointedly observed that he did depend on engineer’s reports “and they…do rely on origin and destination counts.” For her, sound engineering trumped oracular opinion.

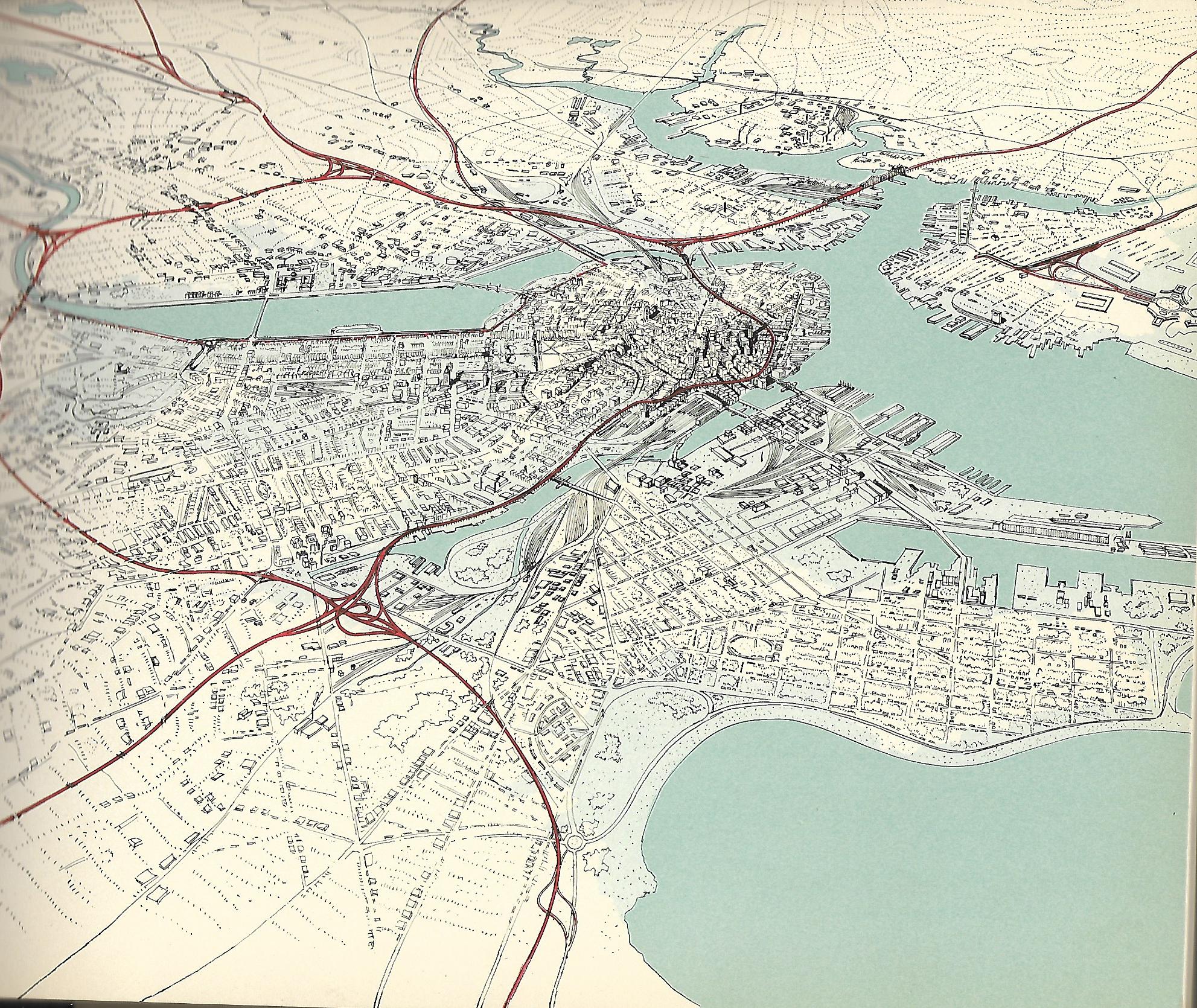

Without benefit of Moses, Massachusetts moved forward a new study, the “1948 Master Highway Plan for the Boston Metropolitan Area” prepared by Charles A. Maguire under the supervision of a joint board comprised of Herlihy; William T. Morrissey, Commissioner of the MDC; William H. Buracker, Commissioner of Public Works; and Harold Duffy as Secretary. The plan was influential in the final passage of Senator Staves’ $100,000,000 highway finance bill, the first of several bond bills for an “Emergency Highway Program” beginning in 1950. The long-awaited Central Artery was an early element of the program. Had the full plan been fully implemented, it would, of course have wreaked havoc on a scale similar to the disruption Moses’s handiwork caused in New York.

1948 Master Plan

Herlihly’s role in the realization of the Artery was acknowledged but this testimonial dinner was much more than that. It was an acknowledgment of her abilities, political acumen, dedication to the public good and her achievements as a nationally recognized planning expert. Her success was even more remarkable in a time when all related fields were overwhelmingly dominated by men. Modesty and gentility wedded to self-confidence and curiosity appear to have defined her. In 1934, when her expertise and skills were already notable, she could still self-effacingly write to Harvard’s Landscape Architecture program for suggestions for further study beyond what she accomplished on her own. ‘Planning is just common sense,” she would tell Louis Lyons, the legendary Boston Globe Reporter, in a self-effacing way, even as he emphasized “She is one of the most widely sought authorities on city planning in the country and is the only woman regularly elected to the American City Planning Institute.”

Despite her roadway planning, she was no single-minded highway champion, and her opinions mattered to decision makers. In 1935, she quickly ended an idea to widen and straighten the Riverway and Jamaicaway parkways. This would have meant massive tree loss and degradation of the Emerald Necklace. She made it clear that the trees were not the cause of “driving trouble. It’s the driver himself…save the beauty and warn the driver to be careful.”

Like other rare successful women of her time, Herlihy’s competence and expertise would necessarily be offered in an unthreatening manner. “She has retained a feminine charm that has made hundreds of staunch friends for her,” wrote Lyons. “A woman need not be masculine to hold down a man’s job. That is another superstition long ago exploded,” she explained. And in a time with limited options for bright, ambitious women and tightly defined gender roles, she was sanguine about her choice and its cost:

“Well, no one can make a success of two jobs at the same time…Many women are trying to do too much today and are unable to do anything well. It is not fair to expect a woman to be a homemaker and a business woman at the same time. I have not tried to be a homemaker.”

And yet she held homemakers in high regard. When a New York publication asked Mayor Curley to list the top ten women of “greatest achievement,” a list she no doubt would top, she convinced him not to do it, because “everyday mothers of families” equally deserving of honor were not eligible.

Throughout most of her life she lived with her sister‘s family in Everett or her brother’s family in Jamaica Plain. It is curious to us today that such an accomplished woman influential in her times and consequential to our cityscape is now nearly forgotten. Her modesty and endurance is an interesting contrast to her contemporary, William F. Callahan, the master builder of Massachusetts highways. Like Herlihy he also began as a stenographer with big ambitions. His career rose and fell to rise again and he was dogged by controversy and shadows of corruption. He bullied through by his will and stubbornness. She was equally ambitious in her own way but she didn’t dominate headlines. Her thoughts were several paragraphs in, but generally the most considered and reasoned. His name lives on in concrete; hers is found in footnotes. Perhaps it’s because for her the joy was in the doing and not the recognition. “When one is absorbed in one’s work, it is not hard” she simply explained.

Fantastic! Fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this! And for highlighting such an influential woman! Fantastic!

LikeLike

Great article.

LikeLike

Thank you! Elizabeth is my Great Great Aunt. My father often speaks fondly, and with great awe, of her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks to you. I’m very pleased that you liked it. It was fun to research and write and she is such an interesting and endearing personality, not to mention trail blazer. I came across her name repeatedly in my professional life and decided it was time to “discover” her.

LikeLike

Fascinating article about a quiet trailblazer. I think it’s long past the time that Ms. Herlihy should be publicly recognized by Massachusetts.

LikeLike