One humble street provides a window into another aspect of the neighborhood’s life and history

“Where’s Hamburg Street, sonny?”

One October day in 1918 at the height of the Spanish Flu epidemic, the patrician George S. Baldwin, a wealthy Brookline stock broker, was escorting public health nurses and found himself flummoxed as he tried to locate Hamburg Street in Boston’s sketchy South End neighborhood.

Hamburg Street—more alley than full-fledged street—would be difficult to locate on a good day, but today it was particularly well-hidden and apparently nowhere to be found. Credit for the confusion lay with a gang of local boys. They had pulled down the offending street sign with the provocative “Hunnish” name and replaced it with a handmade placard proclaiming their tenement alley “Ryan Street” in honor of Thomas A. Ryan. Tom, a 22-year-old local boy born on the street, was cited for gallantry earlier that year during the second battle of the Marne but was tragically cut down on July 23rd in an assault on a German machine gun position outside Chateau Thierry.

“Diss uster be Hamburg Street but it ain’t no more…us guys heard that Hamburg is a German city and we’re all reg’lar American guys round here, so we jist renamed the street Ryan, for Johnny Ryan (sic), who died fightin’ to get to Hamburg!” or so the Boston Globe entertainingly enlightened its readers in a questionable recounting that didn’t even get Ryan’s name right. A Boston Post account was less colorful and likely no more accurate than the dubious Globe reporting. In the Post’s version the kids, sounding as though as if they’d just rowed in from Harvard’s Weld Boat House, announced: “We fellows couldn’t stand for that German name. We changed the name to Ryan Street for the first one of our boys from here to be killed in France.”

Baldwin wrote of his discovery to Mayor Andrew J. Peters, the Democrat who’d defeated Michael J. Curley the year before in a heated four-way race. A shrewd Peters, saw the political value in supporting the boys initiative and made the change official the following January and for good measure, he eliminated German names from three other streets, renaming all for fallen heroes. Honoring war heroes was always good politics, and the astute Peters perhaps garnered some good will on Curley’s turf, if not with with Curley who, in his inimitable style, would later dismiss Peters as:

“…a part-time mayor with a passionate addiction for golf, yachting, hammock duty and other leisurely pursuits, and although a man of mighty moral muscle and admitted courtliness, he deserved the censure even his friends heaped upon him when they called him ‘an innocent dupe for a conscienceless corps of bandits.’”

It couldn’t have hurt that the Ryan clan, headed by Tom’s father, patriarch and brick mason Martin Ryan, was politically inclined. Tom’s older brother John, also a mason, would serve as the business agent of the brick-layer’s union and later, breaking with Curley, serving as rival Maurice Tobin’s campaign manager.

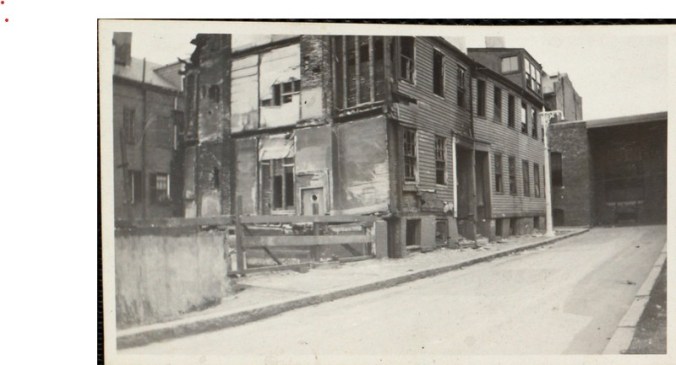

Alas, Tom’s honor would last even less than Tom’s own life, because even in 1918 the ultimate demise of Hamburg/Ryan Street was inevitable. Short, narrow Hamburg Street stretched from Mystic Street, the alley that paralleled Washington Street, and spilled out to Harrison Avenue, with direct access to the expanding wharfs and piers along the South Bay. For the previous 50 years, gritty Hamburg Street was a focus for reformers, progressives, and do-gooders of many stripes and competing motives, but always to limited results. About fifteen feet wide, the street and its houses were substandard in countless ways, including hazardous construction and basic provisions for light, air, and drainage. The ultimate solution to the physical problems of the street would arrive in the New Deal era in the complete removal of the neighborhood under the rubric of “slum clearance.” But the site would sit empty; new replacement housing would wait another decade to be realized. The obvious solution to poverty would remain more elusive, foremost “low wages, of course, …often a prime cause …oftener than capitalistic philanthropists are ready to admit …“

“everyone was under the impression that [the South End] would become one of the most solid residential sections of Boston.”

This is a kind-of biography of a humble street that belies the notion of the South End as only a once elegant, exclusive enclave of wealth and prestige that fell on hard times. The grand bow-front houses and leafy squares were certainly elegant and wealth abounded and it did decline over time, but these qualities were just some aspects of a neighborhood that was economically and socially diverse from its beginnings. Some of the poorest parts, like Hamburg Street, in fact predated their grander neighbors by several years. This blinkered view, deliberately or unconsciously, was persistent and conditioned by historic and even fictional accounts, even as the posh streets and humbler corners grew up together; the latter never warranted much scrutiny save for the occasional scandal or tragedy.

Popular fiction of the late 19th and mid-20th centuries perpetuated the misapprehension of the South End’s precipitous decline. In William Dean Howells’ The Rise of Silas Lapham, Lapham, a canny Vermont Yankee, “bought very cheap of a terrified gentleman of good extraction who discovered too late that the South End was not the thing...” In the witty satire, The Late George Apley, by John P. Marquand, the aristocratic Apley family made a panicked escape when George Apley’s grandfather encountered a neighbor in shirtsleeves. “Your grandfather had sensed the approach of change; a man in his shirt sleeves had told him the days of the South End were numbered…he sold his house for what he had paid for it and we moved to Beacon Street.” George Apley’s uncle rued that “everyone was under the impression that [the South End] would become one of the most solid residential sections of Boston.” And of course it was, just not in the way the writers would have it.

The architectural critic Bainbridge Bunting, no apparent fan of the South End, is one of the few critics to capture the South End’s actual composition. His “Houses of Boston’s Back Bay” describes the South End in this unflattering but accurate way: “It unfolds itself by isolated residential blocks. And because the district is so lacking in continuity, one is hardly aware of the variations in the quality of the building; mansions cluster about Chester and Union parks indifferent to factories and wooden tenements only a block or two distant.”

Writing in 1906, Albert Benedict Wolfe’s “The Lodging House Problem in Boston,” observed “No part of the city assumes a more deceptive outward appearance… [the houses] look like the mansions of the moderately rich and well to do.” But Wolfe was only concerned with the grander houses of the avenues and squares, Hamburg Street was assigned to the “tenement district” and in his assessment the decline was not the proximity of existing housing of the working class.

The tremendous decline of South End real-estate values is an incontestable fact. We have already said the decline began on Columbus Avenue and was due to the crisis of ’73…in Union Park also the decline began soon after that year. The crisis was undoubtedly the prime cause for the depreciation setting in. the impending opening-up of the Back Bay lands removed any hope of recovery.

As proof, Wolfe charted the decline in property values on Union Park (and only Union Park) from 1868 to 1905 which demonstrated a near 40% decline but notably over four decades. He tempers this assessment with the observation that,

An old house is not supposed to bring a high price…Some decline in values in the South End would probably have occurred …

To further explain that inevitable decline he quotes another writer, who explains,

When the public have been educated to prefer light stone or brick houses to the old-fashioned brown-stone front, and modern interior arrangements, and decorations, and plumbing to former styles of equipment, the old value of the house has about departed.

“the most desirable part of the City for genteel residences”

In the early 19th century, as the city migrated further south, it inched towards the thinly populated Neck, the marshy isthmus that served as the land bridge to Roxbury and would become the modern South End. In 1801, well before the fill reached the Neck, the architect Charles Bulfinch prepared a plat for the area. In Boston, A Topographical History of Boston, Walter Muir Whitehill writes of those early years and suggests that this area “showed momentary promise of attracting purchasers who wished to have rather more land around their houses…” He wrote fulsomely of the Deacon House of 1848, a one off and particularly grand house and an example of a potential for which there were few takers. The Deacon House had arrived late to the party; the South End was already heading in a different direction. Impressive attached house rose around Franklin and Blackstone Squares in close proximity to the simpler wooden houses on Hamburg Street but nothing again matched the grandeur of the Deacon House. The street plat would be updated in the early 1840s and the revised plan formalized in 1850. This new plan in 1850 split the Bullfinch plan blocks with new parallel streets and created smaller lots which would prove better suited to attached middle-class row houses that would come to characterize the neighborhood. The historian Nathaniel B Shurtleff in 1871 recounted the success of the new approach, just a couple of years before the purported decline in A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston:

“Plans and estimates were made by Messrs. E.S. Chesbrough and William P. Parrot, skillful and experienced engineers, and from this time the South End began to be ‘the most desirable part of the City for genteel residences”

Yet, just a few years before in 1843, the Neck had already attracted builders of economical wooden houses on newly established Hamburg Street. These compact, closely packed houses were easily visible from the Deacon House. An 1835 change in Boston’s already minimal fire regulations allowed construction of wooden houses without masonry fire breaks in certain neighborhoods, including the Neck. This relief might have been a response to a housing crisis driven by the decline of older neighborhoods in the North End and Fort Hill. In a reaction to a sudden demographic change, the native Yankee population and their families fled the deteriorating conditions as absentee and avaricious landlords packed in new, often destitute immigrant tenants. In “Boston Immigrants”, Oscar Handlin references a contemporary report on the public health and the dismal conditions of Fort Hill:

“…immigrant homes…were not occupied by a single family or even by two or three families; but each room, from garret to cellar [was]… filled with a family… of several persons, and sometimes with two or more… Every nook was in demand. Attics, often no more than three feet high, were popular. And basements were even more coveted, particularly in the Fort Hill area; by 1850 the 586 [basements] inhabited in Boston contained from five to fifteen persons in each, with at least one holding thirty-nine every night.

New affordable locations, like Hamburg Street, were brief options for the native working class to escape the change to the old neighborhoods but this phase would only last an instant. The Chesbrough plan introduced an important innovation—mid-block alleys. These rear passageways greatly improved light, air, and overall livability. Unfortunately, well before the new plan could be implemented, Hamburg Street already sat right where the mid-block alley might have been. What’s, more, its tiny 20’x 40’ lots of 800 square feet pinched the lots of the neighboring streets making the surrounding neighborhood denser and closely packed. The combination of flammable wooden construction and tightness would bring worsening conditions and perils over time.

Initially, things were going according to the simple plan. The 1846 city directory listed 20 heads of Hamburg Street households, all tradesmen, who easily met the desired criteria of the rental advertisements as suitably “genteel” neighbors. They included machinists, carpenters, a pianoforte maker, three housewrights, engravers, blacksmiths, and masons, with reassuringly Anglo-Saxon “American” names such as Sargent, Watt, Worcester, Yeaton, and Coffin. But this careful social order would last only briefly because a “Yankee flight” from the city was underway.

“…the South End, still a desolate marsh … was yet too expensive and inconvenient for the slum dwellers of the North End and Fort Hill.”

The houses of Hamburg Street were not intended as tenements, but rather modest “low-price” houses for “native” tradesmen and small businessmen. Their five rooms – sometimes seven- per side- with attics and basements , and Lake Cochichuate “aqueduct water,” were suitable for a “small family.” One 1847 advertisement for one half of a double house assured potential renters that the other half of the house is “is now occupied by a small genteel American family.” The rents of $80 to $100 a year or $10 to $12 a month, were well beyond the reach of an financially insecure immigrant laborer making at best $200 to $300 a year.

Just a few years later the editor of the 1850 city directory editorialized anxiously, “Our city has suffered a great loss of population by the removal of a large number of our citizens to suburban towns. The facilities afforded by the various railroads … have induced many thousands of our enterprising businessmen to reside with their families in the country.”

But, there had been no population decline. In fact the population of Boston had increased from 114,366 in 1845 to 138,788 in 1850,an increase of over 24,000, but the total population wasn’t the concern of the writer; it was the changing make-up the of the city that vexed him. The city’s foreign-born population was now 63,320 – almost 46% – and of these, 52,961 most alarmingly, were Irish. A year earlier in 1849, one anonymous “Joel” put it more bluntly in “The New England Puritan”:

Boston is evidently losing its distinctive character as a metropolis. The city will soon be out of town. So many who have formerly lived here had moved to adjacent places, and so many who do business here now reside elsewhere, that our interest in the place as residents is largely shared by the inhabitants of other towns. And not only so; – one half of the births last year in Boston were of foreigners. We could name of more than one instance in which the occupants of very respectable and desirable courts in this city are removing to other towns because the Irish have so multiplied around them as to make it undesirable to live there. An enterprising Irish landlord will seize upon a tenement of very respectable appearance, and underlet the rooms to an indefinite number of tenants. They go in herds or swarms; and when one house in the place is thus appropriated, the rest fall in value and the place becomes an Irish (sic) neighbourhood…Must we not enlarge the bounds of the municipality so as to include the neighboring cities and thus secure a Protestant balance in the administration of affairs?

By 1850 Hamburg Street already reflected the rapid change. Even with half the house lots unoccupied, the city directory counted 29 heads of household, and of these, 19 were laborers with Irish surnames. What’s more, influx of less financially stable laborers brought a drastic change to occupancy as revealed in the 1850 census. Multiple families crowded into these small houses often taking in boarders to share the burden. Newly-wed Patrick Morgan, a laborer, and his wife Margaret Doherty living with an infant daughter on nearby Norwich Street provide a typical example. According to the census, their house at 9 Norwich now housed three families totaling fifteen souls in a typical “modest house” meant for a “small family.” This was no exception; many neighboring houses were even denser; it was the rare house that sheltered a single family. They would soon join Margaret’s brother Barney Doherty and his young family on Hamburg Street.

But even as they crowded together, conditions for the newer residents of Hamburg Street were preferable to the older neighborhoods. In these earliest years the partially built-up Hamburg Street would have had an almost pleasant openness. This would be fleeting however as the neighborhood expanded and grew increasingly crowded. The new Irish arrivals on Hamburg Street, like the Morgans and Dohertys, differed from the crush of famine refugees crowding into the North End and Fort Hill. Patrick Morgan, from Dublin County, arrived in New York in 1840; his wife Margaret, from Donegal, landed in Boston in 1839 after a year in New Brunswick. While poor, these earlier immigrants were largely from more anglicized east and north of Ireland and they were likely to be better established than the destitute rural poor flooding into the city.

Handlin describes the Neck of this time in Boston Immigrants:

“…the Irish trickled into the area. Their representation nevertheless was limited, composed largely of intelligent tradespeople and mechanics and confined north of Dover Street in a minority among their neighbors. For throughout this period the South End, still a desolate marsh … was yet too expensive and inconvenient for the slum dwellers of the North End and Fort Hill.”

Handlin’s calculations were off some; as the 1850 census showed, Irish were well represented in the new neighborhood below Dover Street. Saint Patrick’s Church was established further south on Northampton Street in 1850.

“…about as ugly, dingy, filthy – contrived and arranged and altogether unwholesome appearing affair as ever man put up for the accommodation of his fellow creatures.”

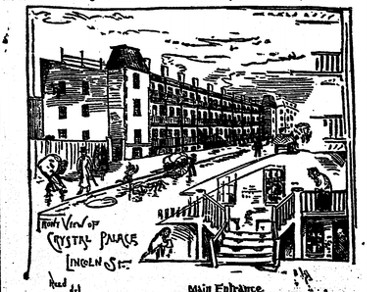

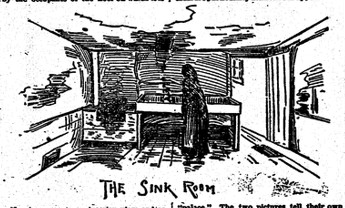

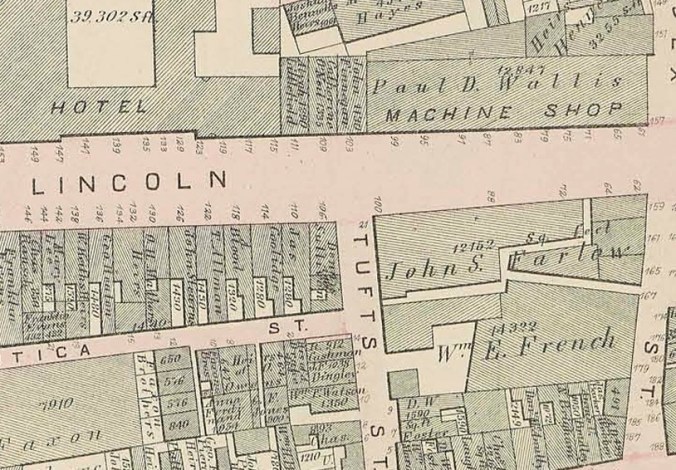

The infamous South Cove slum, the “Crystal Palace” just a mile north on Lincoln Street, a contemporary of the houses of Hamburg Street, offered a horrifying contrast to the meager comfort of Hamburg Street. This notorious tenement was owned by the Newton merchant John S. Farlow, who had acquired the site in 1851 and built what quickly became sardonically known as the “Crystal Palace,” in a mocking reference to the actual Crystal Palace the marvel of the 1851 London exposition. The “Palace” was a block-long, 3-and-a-half-story, teetering wooden wonder backing up to a distillery. Stair towers stood at either end. Open passageways between the towers provided unprotected access to the apartments. It was reputed to house 500 people who shared the three toilets and its basement housed rag pickers, trash and rum shops.

Farlow was born in Dublin to an Anglo-Irish family. He started in Boston as a grocery clerk, eventually graduating to his own business and then adroitly sponsoring cargos in the China and East Indies trade. He later shifted his capital to railroads and real estate speculation. By the 1860s, he had relocated his family from crowded High Street to greener pastures in Newton where he became a prominent philanthropist, helping to establishing the Newton Public Library and gifting Farlow Park to the City. He would later be known as a progressive Republican, a “Mugwump,” and a founder of the Reform Club. Reform, in this case however, focused on tariff policy, not social reform. Farlow, like other speculative owners, practiced hands-off management, usually through lessees or managers, and generally eschewed basic maintenance. He owned the Crystal Palace for its 35 years of existence, it was generally agreed to be the worst slum in Boston. One account in the Herald described the misery in detail.

Families of as many as 10 or 12 persons occupy one or two rooms, and sometimes two families occupy the same apartment. The “apartments” were reached by exterior stairs and walkway. The entire building had just three privies in a trash-filled back yard and a single sink and drain on each floor … To be truthful, the miserable old block is about as ugly, dingy, filthy – contrived and arranged and altogether unwholesome appearing affair as ever man put up for the accommodation of his fellow creatures.

The Palace was a particular challenge to the few reformers addressing the worst of slum housing. In 1871, a reform group of leading Boston citizens formed the Cooperative Housing Association to upgrade existing tenements. Confronting the Palace, the Association leased the tenement from Farlow for $2300 and taxes, but he refused to pay for repairs. The Association took on only “the changes that were necessary for health and decency,” and proceeded to empty the cellar and swapped out the basement rum shop for a “Holly Tree Coffee room” (a low-cost restaurant for the working poor.) Yet by 1876, the tenement and its perilous conditions defeated the Association which regretfully abandoned the exercise as a financial failure. The Association would focus on a new housing complex by Hamburg Street and on other properties in the North End and Dorchester.

Several years later, in 1884, as Boston waited in fear of the cholera pandemic then raging across southern Europe, the sordid conditions at the Crystal Palace again came under scrutiny. In response to a sensational exposé, Farlow was ordered by the Boston Board of Health to correct the squalor or raze the building. He complained that the property rarely produced enough revenue to pay the taxes, and that he kept the building as a “charity” for the poor. Short of demolition, he proposed to lease the site, this time for no cost to Alice Lincoln, the housing reform advocate who managed several model tenements. Behind his seemingly generous offer was the knowledge that he would soon replace the shambles with a more lucrative commercial building. With the United States Hotel a block away and major railroad termini nearby, the surrounding neighborhood was becoming too valuable to tolerate the Crystal Palace. But again Farlow balked at assuming the $15,000 of needed repairs adding that if he took the building back during the lease, he would reimburse Lincoln but she refused the deal. Farlow razed the palace in 1885 and replaced it with a seven-story commercial building. However the replacement had an even far shorter life than its notorious predecessor when the new structure was destroyed in an enormous fire which raged through the area in 1893. The current building on the site was built the following year by the estate of the now deceased Farlow.

By contrast, Circumstances on Hamburg Street were marginally better. Certainly, as the census records indicate, multiple families shared each house, but often the families were related, and each small house included its own water and sanitary facilities. The houses were largely owned by absentee landlords but in a few instances by an owner-occupant, a relative or friend from the old country. Robert McNinch, a laborer himself, was one Hamburg Street landlord. An Ulsterman from Belfast, in time he owned three houses on the street and another two nearby. Yet he and his family lived in his properties amid his tenants. He fastidiously repaired his house after damage from neighboring fires and wisely maintained fire insurance.

“The houses on Hamburg Street were a very poor class of wooden ones…”

Fire was of course a constant threat to the densely packed street of tinderbox houses. The fire journals of daily newspapers reported fires with unfortunate frequency. Wooden houses with no firebreaks were particularly vulnerable, and the call box on Hamburg Street was frequently activated. One fire in 1861 spread across seven houses; another in 1871 stretched across five houses and dislocated 21 families. Fire returned to the same houses the following year.

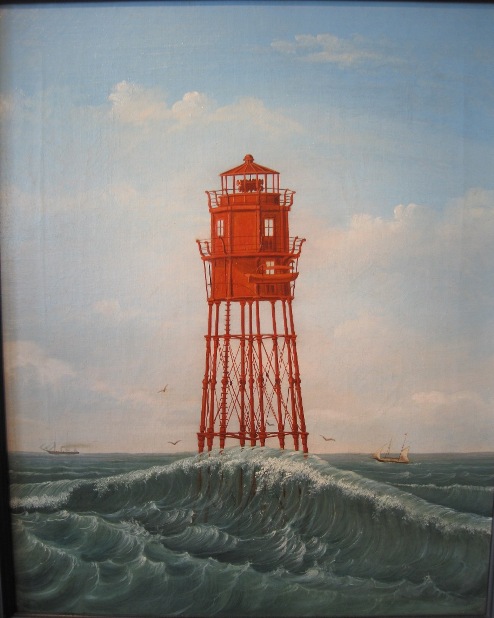

Nature brought other risks. The Great Gale of 1851, a historic storm of epic proportion, slammed the South End and Hamburg Street. The storm is best remembered for the complete obliteration of the two-year-old “indestructible” Minot’s Ledge lighthouse off the coast of Scituate. Two assistant keepers were lost to the roiling waves and battering winds, but destruction also raged all along the coast and deep inland, tumbling chimneys and cupolas and flattening flimsy stables and rear ells. By some accounts, the storm tide was ten feet above the ordinary and deemed the “highest tide ever known.” As it surged onto the Neck, timber and coal were swept off wharves. Lime stored on wharves burst into flames, and in some cases, entire wharves and bridges, including the Neponset crossing, were carried away. The grand houses on Franklin Square flooded with sea water, as did basements from Waltham Street to Northampton Street. In the chaos, on Hamburg Street, Patrick McGreavy’s four cows were drowned, along with two fine horses at the brewery on Northampton Street. Horses, so vital to everyday life, coexisted with people everywhere in the city, jostling with the rich and poor, but in 1851 for a time apparently it was possible to keep cows on Hamburg Street.

“The houses on Hamburg Street were a very poor class of wooden ones…”

A storm like the Great Gale was a rare occurrence, but nuisance flooding was an everyday problem and a plan to correct it would have grave implications for Hamburg Street. The filling of the Back Bay had resulted in regular flooding and impaired drainage in the adjoining neighborhoods. In 1868 Boston solved two problems when it rid itself of the wretched housing conditions of the Fort Hill neighborhood by removing the hill and using some of the material to dramatically raise the grade of the neighboring Church Street district, “Kerry Village” today’s Bay Village neighborhood. This required not only raising utilities and roadways but lifting entire blocks of attached brick masonry houses. The Church Street houses were deemed substantial enough to warrant saving, but when the city continued the effort in 1871 with the so-called “Suffolk Street District” (which stretched south from Pleasant Street to Dover Street.) The city had another goal.

“[The city purchased and demolished all the old wooden buildings , which in their opinion would disfigure the character of the territory….The new Building Law absolutely prohibits the erection of any wooden buildings on that territory so that, in time, the district will be covered in substantial brick or stone structures.”

A few years later in 1875, the city next set its sights on the “Dedham Street District,” the next area in the progression of improvements. It ran from Malden Street to East Brookline Street and between Washington Street and Harrison Avenue. The humble wooden houses of Hamburg Street sat smack in the center of the district and their demise seemed inevitable. The City Engineer Thomas Davis explained:

“The houses on Hamburg Street were a very poor class of wooden ones and when there were unusual high tides the water flowed into some of the cellars so that a sanitary measure was a necessity for the work being done.”

As part of the program, the city would take the houses and offer them to former owners who would be responsible for the cost of the improvements. On Hamburg Street, this would mean the owners would also be responsible for replacing their former homes with new, presumably brick structures. This would be a challenge for any homeowner, but even mores-so in the case of Hamburg Street. By the 1870, Hamburg Street now included five property owners in residence with Irish surnames. Overall there were 48 heads of household, nearly all Irish, which included 27 tradesmen or skilled workers and now but 15 laborers. The Hamburg Street property owners, with a new of political savvy, enlisted the young and ambitious South Boston Attorney Patrick A. Collins, a former state representative and senator and a future mayor, to represent them in a hearing. The owners contested the plan and argued that the city should shoulder the entire cost of the work particularly because their houses were built before the city accepted the street at its current grade in 1861. Mayor Cobb withdrew the legislative petition ending the threat. Hamburg Street was saved—for now.

“I did not know the place was in such villainous conditions…”

Hamburg Street, or at least a small portion of it, came under scrutiny again in November of 1884 in a sensationalized survey in the Boston Herald of the worst slums around the anxious city that their reporters thought to be hot spots for the rise of cholera. The Herald’s florid descriptions were intended to shock and horrify more than enlighten . Although the bacterium Vibrio Cholerae was discovered in 1854 and again independently in 1883, the reporters were of the misguided belief that the disease arose directly from the miasma and the poor habits of the inhabitants. As one wrote:

The odors which [I] encountered were almost overpowering. In the first place the dwellings are so rotten that it is with difficulty that they are held together …reeking piles of garbage lay in the hallways. Immunities of every description hold high carnival on the walls… The sick calls from this building are frequent. They form a large proportion of the entire number in the South End. …On the top floor of Number 4, a little girl lay in a bundle of rags. Her livid face bore indications of the rapid approach of scarlet fever…the cellars of these buildings, and there are eight of them, are simply pest holes. The stench arising from them is charged with pestilence. Here is where Cholera could obtain a good hold… Every now and then one stumbles over piles of garbage. The pathway leading to these houses was in some places ankle deep in mud – a mixture of rotten herrings, cabbage leaves and filth of every description…

If the South End was better off than other neighborhoods particularly the North End, it did harbor a number of notorious tenements particularly along a disreputable strip of Washington Street a few blocks east of Hamburg Street. These included Frank’s Court, the site of today’s Rollins Court and the benign sounding yet ill-famed Temple Park, roughly the location of today’s May Street. The absentee owner of the dubious park, Doctor O.S. Sanders—“who rolls in luxury on Columbus Avenue“—protested that he’d only become aware of the conditions at his property upon reading of them in the Herald’s report. The good doctor explained:

I did not know the place was in such villainous conditions until I visited it early Monday morning … I have not been there three times in the past year. I have been in the habit of placing the property in the hands of an agent, who I supposed looked after the matters in general, particularly the welfare of the tenants…to be candid I have had my fears and have written … to the Board of Health, praying them to be vigilant…”

He was professed to be oblivious although living just a few blocks away, but he was well aware of the value of his neglected property. When asked how profitable the property was, Saunders responded, “Scarcely 2 percent, so you can see for yourself that it is not worth the trouble it has cost me.”

A few blocks away on Hamburg Street two houses drew the Herald’s attention.

The tenements Nos. 26 & 28 Hamburg Street will also bear a visit from the agents of the Board of Health. The filthiness of some of the people connected with the dwellings (sic) have placed them in an entirely unwholesome condition. The reporter caught one woman in the very act of filling the drain in the rear of 26 Hamburg Street with refuse consisting of a part of the entails of a fowl and a general assortment of swill… To see how the inmates of the houses live, one need only take a peep at their back yards, if they can be termed such. Not one of them occupies more than 24 square feet of space. Sick cats lay around in rare profusion. Invariably one corner is occupied exclusively by garbage and ashes. Their closets are also without ventilating shafts, while the whole surrounding (sic) impress the visitor with visions of disease and general unhealthiness… strips of black and white, indicative of the passing away of some precious soul are often noted flitting from the doorbells of these and adjoining dwellings. The attending physician writes out the certificate of burial, giving the cause of death in Latin phraseology. Translated it means either typhoid, malaria, pneumonia, or some malady of a similar nature. These matters attract no attention, seemingly. Avaricious landlords collect their rent with the same exactness …

For the reporters, like the absentee owners and general public, the blame for the repugnant conditions fell equally on landlords and occupants. “ If…tenants looked after their premises as they should, the house would not be in such bad condition …” One Mr. Moore, lessee and manager of sorts of Temple Park, had a ready explanation:

Mr. Moore, the lessee of the property, stated to the reporter that the Herald’s description of the place was truly realistic but he lays the conditions of the affairs to the tenants. Said he, drunkenness, destructiveness and filthiness are characteristics of the class of people who occupy these houses. I should like to know how these people are to be dealt with. They are totally unfit to occupy tenements or model lodging houses. They are naturally filthy and do not know the meaning of the term cleanliness. It is impossible to educate them to a higher standard of life.

Woefully overcrowded and without adequate water, proper ventilation, grossly inadequate sanitary facilities, little or no basic maintenance, and no trash collection, it’s inconceivable how the tenants could “look after their premises…” in any meaningful way. Yet even the principled reformer Alice Lincoln acknowledged that tenants were grossly exploited, but held similar beliefs about them. Speaking at a meeting of the Associated Charities, she observed:

It is useless to do anything for tenants of this class as a charity…. charitable endeavors … on the part of landlord will not be met with any responsive labors on the part of the tenants… The only way is to enforce laws of cleanliness, making the refusal to abide by these laws sufficient excuse to invalidate the lease.

The Herald congratulated itself that its coverage resulted in the demolition of Temple Park with no thought to suitable replacement housing. These properties and their dismal conditions were financially attractive to speculators and slumlords. There was good money to be made. As Charles Eliot Norton explained in “Model Lodging Houses in Boston” in the June 1860 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, housing for the poor was highly lucrative: “No other class of houses gives, on average, a larger return on capital invested…” With no capital risked for basic maintenance and repair, slum housing must have been lucrative indeed.

Administrative or legal remedies were few and inadequate, and their burden fell hardest on tenants. An 1859 Act permitted Boards of Health to condemn any tenement, specifically calling out cellars, should the board find them uninhabitable. If the landlord failed to correct the problem, the remedy was to evict the tenants. If the landlord did neither, the city could order the building razed. With only minimal investment, the landlord could manage the loss and likely profit from the action. For the exploited tenants, the impact was enormous. The Commissioner of the Board of Health later led a sympathetic Globe reporter on a tour of many of the same city-wide sites that the Herald had recorded. At Sands Court off Harrison Avenue in the South End, they were greeted by a scene seemingly lifted out of a popular contemporary melodrama. One old woman, reputed to be near 100 years old, pleaded to the Commissioner:

Oh! For God’s sake sir, I beg of you don’t put me out onto the streets tomorrow… I have no friends and nowhere to go … Don’t turn me out! Don’t turn me out!

“What can I do with a case like that?”complained the Commissioner. “I haven’t the heart to turn that woman out, and still the papers talk about doing our duty…”

“The Irish and German residents too, with their clannish proclivities…”

In the era before the arrival of settlement houses and social work, there were some limited efforts to improve housing for some of the working class. In 1853, following European examples and based upon an investment model, the Model Lodging Houses Association was organized, and it built the first of three model tenements in the South Cove on Osborn Place, off Shawmut Avenue. Like the poorly regulated speculator-owned tenements, model lodges charged market rents for small spaces, but the houses featured superior construction, improved hygiene, and careful tenant management, which deliberately excluded the immigrants who lived in the poorest conditions. As the Boston Herald explained in 1855:

“The Irish and German residents too, with their clannish proclivities, would like to live together in this manner… subterranean abodes and miserable damp underground tenements would be abandoned… But first the experiment must be tried by the middling class…”

One investor owned model lodge on Union Park Street was “occupied by American families.” It was claimed that there were other “model lodges” but the exact number was disputed and many that were called “model” were anything but.

The association’s model lodges were not meant as a charity or subsidized housing but intended as a market based initiative to demonstrate to conscionable real estate speculators that suitable housing could provide a reasonable return on investment. The association promised that their model homes would eliminate sanitary and health problems and still provide their investors with a 6% annual dividend. The problem was that slumlords could earn much more.

Coincidentally, the best documented and most substantial examples clustered in the neighborhood surrounding Hamburg Street. In emulation of the Model Lodge Association, the financier and merchant Abbot Lawrence left $50,000 in his 1855 will for the construction of similar model lodges. Norton, again writing in The Atlantic Monthly, expressed the hope that the Lawrence bequest would expand the experiment by building for the very poorest classes, but this would not be the case. The first two Lawrence Lodges were built on Harrison Avenue by Kneeland Street in 1861. But as the commercial district migrated into this neighborhood, the Lawrence Lodges were sold, and in 1875 the trust built four new lodges on the west side of East Canton Street, a block from Hamburg Street. Here they joined a complex of 39 three-story houses on the east side built three years earlier by the Cooperative Housing Association. Despite its name, The Association was not an actual cooperative but rather a corporation offering a 7% dividend to its civic-minded investors. The 1880 census returns unfortunately revealed that the model lodge “experiment” had still not been extended in any meaningful way to the “clannish” Irish and Germans or other members of an increasingly diverse immigrant community. In 1880 the residents of the Lawrence Lodges were solidly American. Just two German families and one Irish family were represented among the 49 tenants. The Cooperative Association tenants were similar, counting four Irish, two German, and one Portuguese family among 38 tenants. Although the Cooperative’s first endeavor was the failed attempt to rehabilitate the Crystal Palace, it would manage a substantial tenement in the North End and new construction in the South End, Roxbury, East Boston and Dorchester.

“…if the street has not brightness, it has scraps of picturesqueness…”

The Herald’s turgid description of two houses on Hamburg Street was not a fair or accurate depiction of the overall place nor its normalcy and vitality. In that same year of 1884, in the midst of the baseball craze and cholera panic, the street could sport its own team called the “Hamburg Stars,” who were eager to play the team from Boston College just up Harrison Avenue. A better illustration was a fictionalized portrait of the neighborhood written in the early 1890s by the journalist Alvan Sanborn, “The Anatomy of a Tenement Street,” in Forum and Column Review in 1894. His “Bullfinch Street” like the actual Hamburg Street, was overwhelmingly Irish and Irish American. Still in his twenties and a few years out of Amherst College, it was published while Sanborn was a resident and worker at the nearby Andover House. The Andover House opened in 1891 in a handsome bow front on Rollins Street. It was a vanguard of the new “higher philanthropy.” If charity or “lower philanthropy” was to “put right what social conditions had put wrong” this new approach would “put right the social conditions themselves.” and was populated by well-meaning divinity and other recent college graduates who would apply the principles of the new scientific study of sociology. It later merged with a similar group to form the South End House and relocated to Harrison Avenue at the corner of Malden Street, just around the corner from Hamburg Street. The inspiration for Sanborn’s published writings must have been the requirement that workers become closely acquainted with, and profile assigned families. Young Sanborn had greater literary ambition than producing a mere clinical assessment or data collection. He clearly had a fondness for his subjects as he chronicled in a colorful, if often condescending way, their rocky path to assimilation and economic mobility.

Sanborn’s fictionalized accounts – he published an identical account of “Turley Street” in his “Moody’s Lodging House and Other Tenement Sketches-” had greater literary ambition than merely clinical accuracy. His subjects, even when American born, were utterly foreign to his reader; he thus made them comprehensible by likening the street to a New England village. The 20th Century writer Herbert Gans would undertake a similar profile sixty years later in his in-depth study of the Boston’s West End, “The Urban Villagers.”

“During the thirty years or more of its comparative seclusion, Bullfinch Street has developed a life of its own, that is far from being the dull, inhuman thing that popular opinion assigns to a tenement-house district; and this life resembles no one thing so much as the life of a typical New England village.”

“…if the street has not brightness, it has scraps of picturesqueness – a dormer window to which a discouraged plant or two is clinging; a shingled, unpainted, weather-beaten house side bearing a dove cote and green trailing vines; and terraces of roofs crouching about the base of a lofty church with true old-world humility.”

He did write thoughtfully and knowledgably of the causes and sustainers of poverty and the precarious economy of the working poor. He cited foremost “low wages, of course, …often a prime cause …oftener than capitalistic philanthropists are ready to admit …“ He recognized the effects of intermittent or inconsistent work, death and debilitating illness, the latter which he likened to a kind of death. But like his peers he still suggested that the poor are somehow responsible for their lot, so he included unreliability and “improvidence” as well as “overproduction of children.”

“Whether the children live or whether they die they are about equally expensive. The more desperate the family circumstance the faster the children come.”

And of course no 19th-century reformer’s list, no matter how enlightened, would be incomplete without “chronic intemperance, laziness and desertion by the husband.” Like other contemporaries, Sanborn disparaged charities “which paralyze effort.” However in a critical misunderstanding, Sanborn wrote that “the saddest feature of this life is, oddly enough, the very thing that makes it superficially bright – the perfect content with a low standard of living which springs from an extreme poverty of ideals. Sanborn, however, was a tourist to poverty so misinterpreted resignation to one’s lot for contentment.

Surprisingly he was contradictorily critical when his subjects demonstrated any material striving.

Besides the progress of the younger generation, shown by its eschewing manual labor, are occasional signs in the change of taste or in the code of etiquette of the elder. A house that makes any pretension at all to gentility is pretty apt to have some gaudy plush furniture and a few cheap lithographs or chromos. It is sure to have a plush album..

He presents his subjects as naively self-reliant in his cloying observations.

But the most significant expression of the spirit of village-life in Bullfinch Street, and a truly beautiful one, is the readiness of neighbors to help each other out or trouble…Eighty year old Bridget Mulcahy, toothless, but still bright eyed, may be seen almost any fair day smoking her pipe on the stoop of No. 20. Her husband, Jim, a day laborer died eighteen years ago. For seven years before his death he was blind, and his misfortune, joined to his good-nature made him a favorite. Soon after Jim’s death, Bridget dislocated a shoulder, thereby permanently losing the use of her right arm. She became destitute. The neighbors lent her many things…and… Michael Rowe, who was himself behind in his rent, gave her a home in his family. Then her friends, “The Boys from Ireland,” ”put up” a raffle for her which netted $40. She rented a cellar room…and took in two girl lodgers …she has depended largely for her support upon the raffles which the “boys” have continued to “put up” for her once or twice a year.

He’s surprisingly admiring of the role of the Catholic Church in a poeticized, if mawkish, tone.

Furthermore, the church, and the church only, to any considerable degree, diffuses the warm glow of ritualism over a life otherwise would have little beauty of poetry in it.

Sanborn, with his literary ambitions and fictionalized overly colorful portraits, if not the most reliable narrator, is still as one of the few recorders of the world of Hamburg Street. Streets like Hamburg Street rarely merited attention except in the instance of a tragedy or threat. Sanborn’s creativity would take freer flight untethered from Hamburg Street in his “Meg McIntyre’s Raffle and Other Stories” of 1896. Sanborn, ever the romantic, would depart Boston for Paris as the correspondent for several publications and in a heroic gesture, joined the French Foreign Legion.

Above: The limits of the South End per the South End Joint Planning Committee. Boston Globe 11-1-1938. Below: Boston Globe 8-5-1940

“It has been erroneously stated that all the difficulties in the way of erecting the South End housing project have been compromised.”

Hamburg Street remained stubbornly Irish, Irish American or Canadian into the early 20th Century. The surrounding streets were much the same, even as the South End beyond the confines of this narrow alley was transforming with successive waves of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, Russians, Italians, Greeks, Syrians, Lebanese, Armenians, and Chinese, along with African-Americans migrating from the Caribbean and southern US states. Even as it seemed to resist change, Hamburg Street was slowly disappearing. The shabby wooden houses disappeared at an increasing pace, replaced with empty lots which afforded a new playground on one lot in 1902. Families moved up and out to new more desirable housing across the South End and to far-flung neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Jamaica Plain. Even in 1918 when those neighborhood boys rechristened their street, more than half the houses were gone. In 1920, only 13 occupied houses remained. In 1930 there were just eight, and that number dwindled further to three in 1937; the following year there were none.

The accelerating rate of removal was deliberate. It was the fortune of Hamburg/Ryan Street to sit at the center of an area identified for what promised to be one of the first federally funded low-income housing developments of the New Deal era. What fire, storms, disease and other disasters could not accomplish, the new low income housing of the New Deal era would attempt. In the South End, attention of “The South End Joint Planning Committee” – a WPA creation made up of 33 neighborhood organizations- fell to a familiar spot, the super-block defined by East Canton Street, Mystic Street, Malden Street, and Harrison Avenue, essentially the “Dedham Street District” targeted in 1875 and a site in sore need of redevelopment. The Federal Government acquired the site in 1937 and began clearance in 1940. Another project, the Lennox Street Houses, went forward amid protests that the neighborhood was being short-changed, claiming the Lennox Street site was actually in Roxbury rather than the South End. Significantly, the Lennox Street development was the only new public housing deliberately opened to African Americans.

Ryan Street would not go easily. The plan for replacement housing would prove nearly as stubborn to realize as the past efforts to reform the neighborhood and the cleared site would remain empty for a decade. The intervention of World War II had meant delay but the wild inflation of the post war years and dueling bureaucracies nearly killed it. Inflation had increased the per unit cost of the planned housing substantially to $7500 above the $5000 maximum of the Federal Housing Authority, number which was not adjusted for inflation The Feds refused to proceed and the site lay fallow. In 1947 seeking to rescue the project, the City proposed to build the development through the Commonwealth’s new $200,000,000 Veterans housing program. And again the Feds tossed another stumbling block, demanding that they be reimbursed for the $1,500,000 cost of site acquisition and demolition. The city countered that it had lost $146,000 in tax revenue each year that the site sat empty. In an ironic twist, the state housing authorities asserted that the Federal costs for site acquisition and clearance, exceeded the state’s limit. Converting the project to a state funded veterans project brought more complications as the State Housing Board rejected the high rise plan insisting on buildings of three stories. Occupancy too would be restricted to veterans families only. The Federal Housing Act of 1949, the “Slum Clearance” Act which would initiate urban renewal on an unprecedented scale would prove to be the funding solution allowing the development to proceed in 1950 at long last. The result was the 800 plus units of the Cathedral development, now the Ruth Lillian Barkley Apartments. Now 75 years old, the complex has lasted nearly as long as Ryan Street’s near century of existence.

Very interesting!Jonathan

LikeLike